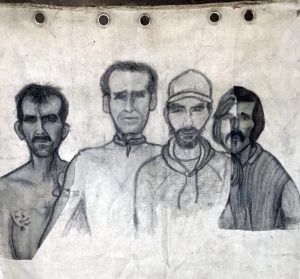

Family

Eddie, Mike, Billy, Donald

Eddie, Mike, Billy, Donald

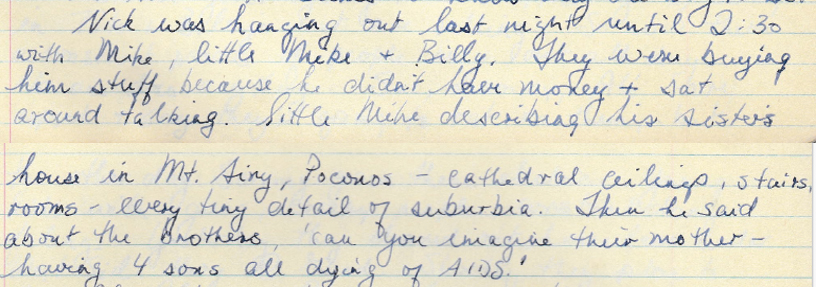

(Gabriele’s journal – June 4, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – January 20, 2022)

At the knife fight that didn’t happen, White Boy had revealed himself to me. But why? Why was the gang giving me his identity, and why, after almost three years of pursuing the story, did the story now appear to be pursuing me. I understood the answer even as I posed the question.

It was called ”life mark” because it was a permanent scar that ran ear to ear on the throat across the Adam’s apple. Also known as the “crack smile” because it seemed exclusively to brand those addicted to a crack-cocaine life who had participated in a rip-off or some other transgression against a drug dealer.

After knowing the story, I understood the meaning, the abject terror, that one particular element of the WHITE BOY tag radiated. Depending on the color of the building or graffiti that the tag scarred, the WHITE BOY slash was always in black or white spray paint. Except for the band enclosing the bottom half of the tag. That half-circle was not spray paint. It was a blood-red brushstroke. The red of the stage blood White Boy had spit on me. The red of the blood beneath the “crack smile” scar. “You know nothing!” White Boy and the corrupt cop Frack had shouted at me. But the truth was evident now. And the truth was I knew too much.

Only later did I realize in horror that my actions had also put those I loved in peril.

When we first started living on the Hill, the policing was done by the heroin addicts who had set up camp there. Most of them had known each other for years, having first acquired their habit in the same small Jersey suburb. Brothers Eddie, Mike, Billy, and Donald were chief enforcement officers, with Eddie being the beat cop always on patrol at their compound.

Eddie slept on the Hill most nights, standing out front and center during the day, monitoring all traffic in and out. Everyone called him the “old washerwoman” because he was also gossip central, always knowing who scored when. One of the laws of the loosely knit pirate gang on the Hill was always to share their bounty, but this rule was constantly being broken. When that happened, “the brothers” collectively confronted the transgressor with a threat or immediate punishment. Although violence was always a possibility, ostracization and being excluded from the shared bounty of the Hill gang was the greater fear that kept everyone in tentative compliance.

It was difficult not to be distracted while talking to Eddie. A large wart dangled at the tip of his right nostril, creating a clown nose that was impossible to ignore. Overall, he resembled Bluto from the Popeye cartoon. Although an imposing figure, no one took his aggressiveness and bullying seriously.

Brother Donald was the Fredo of this Corleone family. Others in the Hill gang, even his own brothers, mocked his work: “You either live the life or you don’t.” Donald made his living with a beggar’s cup on the off-ramp of the Manhattan Bridge and other traffic stops. He repeatedly told the story of how Don Johnson once stopped and gave him his Hawaiian shirt with the admonition, “Don’t you sell my shirt. You keep it.” His pride was that his son was still wearing the shirt to that day.

Brothers Mike and Billy were of a different caliber. They were not on the Hill often, but their joint presence most often meant that somebody had disrupted the world order and some action might be necessary to reestablish discipline. Unlike their brothers, Mike and Billy didn’t say much, but everyone sensed they were dangerous. Their numerous jailhouse tattoos, including the LOVE-HATE on Billy’s knuckles and the blue teardrop tattoo under Mike’s left eye, meaning he had murdered someone in jail, conveyed how deeply prison was ingrained in them. In most ways the Hill was structured as the external extension of that prison life. There was no doubt that it was the white brother addicts who ran the cell block. But these brothers had no resemblance to the Aryan Brotherhood you find in prison. They all shared not only huts but needles with the other Hispanic, Black, and Asian addicts who lived at or visited the Hill. When Gabriele and I first arrived, everyone lived in relative harmony. Thinking back, this was largely because no buying and selling of drugs was allowed on the Hill.

We were all around the same age and they accepted “Nicky,” “Chief,” as one of their own, because he was. And yet, he was not.

I knew this family of brothers like I knew my own. As the oldest, I had led all four of my brothers into “the life.” From delinquency to addiction to jail to prison. We all, in our fashion, eventually broke away. Although no one ever fully escapes, unless it’s the way my brother Steve did, dying young as a heroin addict.

The dead ones haunt and hunt you more than the living. They inhabit your dreams even more vividly than they did in life. On the Hill, without fully understanding it on a conscious level, I was reliving a certain period of my life when my brother Steve with his heroin addiction had become the whole of both our lives.

I was two years older than Steve. Throughout our childhood, through our teenage years, we were mostly inseparable. We grew up on a farm in an extended family that included three other households of uncles, aunts, and cousins. Outside of school, we spent most days as children playing on the farm with the six cousins our age.

But unsupervised after our parents divorced, we found kinship, not with our cousins, but with the other kids who were also raising themselves. The Popovich brothers, Nick and Bob, were a short walk up the country road from us.

The Popoviches lived across the street from our town’s bowling alley and pool room. This was the closest the northside of our small town had to “the street.” As the four of us grew into adolescence together, we found our hustle there. First in the pool room with its accompanying minor mischiefs and fights but progressing quickly into delinquency and real crime.

Long before we were old enough to drive, we were stealing cars for joy rides. Certain years and makes of cars back then were easy pickings. No real skill or tools were needed, just a large screwdriver stuck into ignitions in lieu of a key.

Attached to the loose gang of brothers Eddie, Mike, Billy, and Donald, were others who had grown up in the same Jersey suburb. One of them they called Billy Toyota. He was christened thus because as adolescents in their small town he periodically showed up with a stolen Toyota to drive the gang around in. I thought I left behind the memory of the makes of the cars I had stolen as a teenager. I thought I had left behind the memory of that life altogether. Billy Toyota and the others on the Hill confirmed I had left behind nothing.

I could see the story of these adolescent delinquents as clearly as I remembered my own. I began to see all the life-ending, or at least life-changing, acts performed on the Hill as events that were fated long before they occurred. There were no accidents, only the completion of the story.

At the time, I thought my arrest was merely the result of an impulsive act on my part. Or to quote Frick, “You dumbass.” But more than two years later, after my encounter with White Boy at the corner, I finally understood how Frick and Frack homed in on me early on so as to use me as their patsy later.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link.