The Hill – Project Overview

Thanksgiving 1990 – August 17, 1993

“If I examine my work, I now perceive in it, patiently pursued, a will to rehabilitate persons, objects and feelings reputedly vile… I was involved in the rehabilitation of the ignoble.”

– Jean Genet, A Thief’s Journal

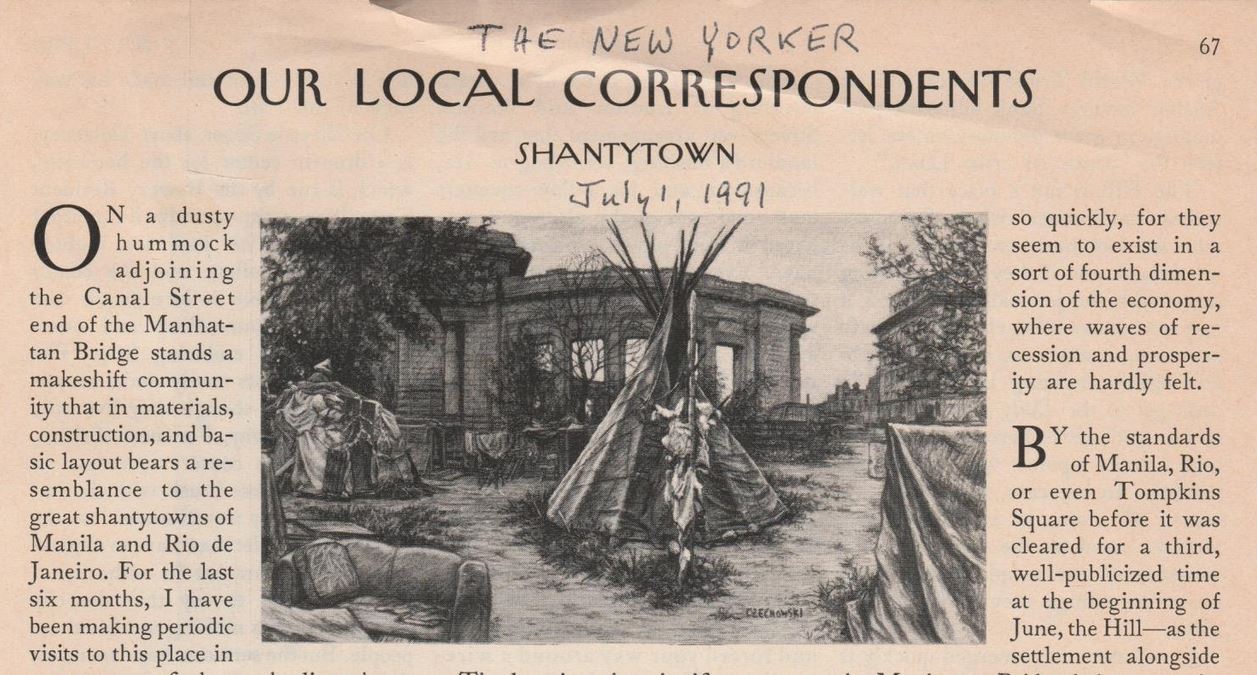

By the late ’80s, homelessness was rampant in New York City. Tompkins Square Park and Bryant Park were tent cities and shantytowns were everywhere. The oldest and most prominent one was at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge at Canal and Chrystie Streets. Roughly 80,000 vehicles a day saw this encampment known as The Hill as they crossed the bridge from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

The year 1990 marked the centenary of the Wounded Knee Massacre. In commemoration, Gabriele and Nick installed a replica of a Lakota tipi in the center of The Hill and moved in on Thanksgiving Day. That same weekend Dances with Wolves opened in theaters, hailed for reversing film’s trend of negatively stereotyping Native Americans, nomads who lived in temporary shelters as a community.

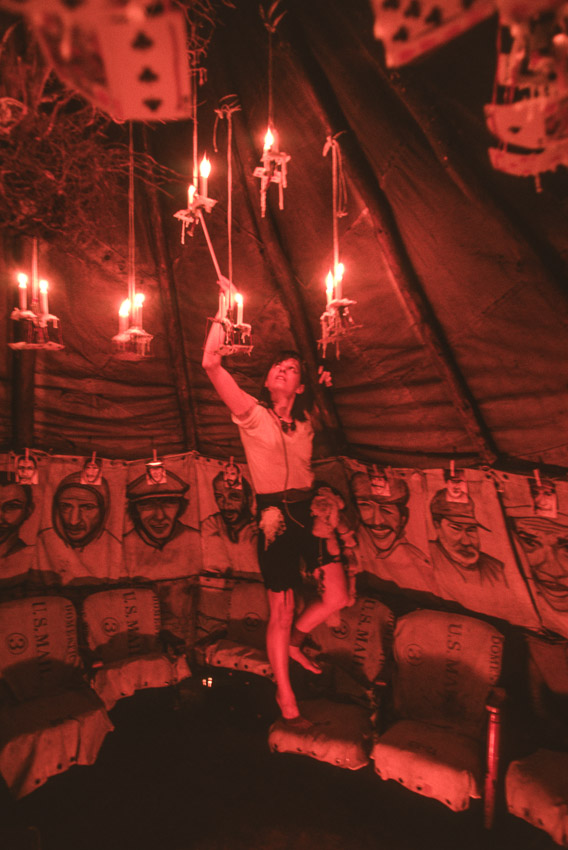

Gabriele sewed the tipi using 78 U.S. Domestic mailbags (referencing both the canvas the U.S. Government distributed to Indians to replace buffalo skins and the number of cards in the tarot deck). It was erected with 17 trees, 25′ tall and harvested in the Catskills, forming an imposing, incongruous structure that could be seen all the way from Houston Street. They dedicated it on December 29, 1990, the centenary of the Massacre, “in remembrance of the lives lost in 1890, and in recognition of the sovereignty and dignity of the most disenfranchised and forgotten members of our society a century later.”

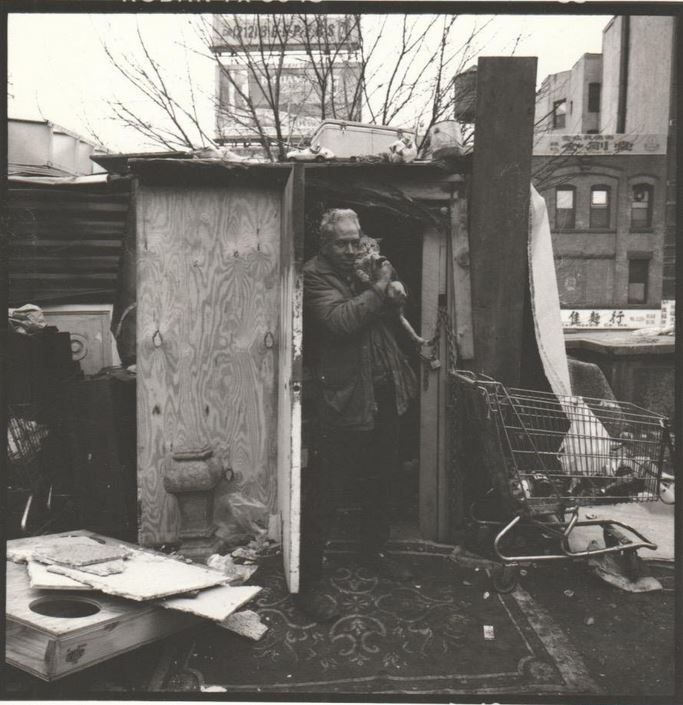

What the casual onlooker didn’t understand — the inconvenient truth — is that residents of The Hill didn’t consider themselves “the homeless.” They, like Gabriele and Nick, had choices. Most had family, friends or other ties to mainstream communities. They weren’t interested in the shelter system or in anyone “solving their problem.” Some were drug addicts who supported themselves through theft or begging. Some were entrepreneurs working hard all day at odd jobs or converting the city’s ample discards into profit at flea markets. Some were ascetics who just wanted to be left alone.

What is society — which has a bias towards conformity — to do with them? Do they have any rights if they don’t have a mortgage/rent payments and are on public property? Should they be pitied, shunned, punished, admired as iconoclasts? And if art’s job is to reveal and contextualize, what is its responsibility?

Nick and Gabriele had a long history of making radical, socially engaged art, supported by their day jobs. At the time, Gabriele worked in the Corporate Finance department at Rothschild Inc. under Wilbur Ross, then known as “The Bankruptcy King,” later Trump’s Secretary of Commerce. Every night after her shift on the 52nd floor of Rockefeller Center, she left work in a black car that dropped her off at the shantytown, where she and Nick would live for the next two and half years until the story of the Hill’s tragic end.

In her journal — available from Autonomedia, Printed Matter, Amazon, or from Gabriele directly (USA only) — she details their day-to-day lives as they navigate one of New York’s largest-ever police corruption scandals, city politics in the Dinkins era (elected to clean up the homeless problem), drug dealers, the AIDS crisis, and the media. It traces the steps of how a shantytown went from the anonymity of waist-high huts hidden in the weeds, to a tour-bus, school-group and celebrity stop; from addicts and recluses just getting by, to a drug supermarket; from a close-knit encampment, to a crime scene that entangles everyone from drug dealers, to users, to cops, to the artists themselves, when one day the unspeakable happens.

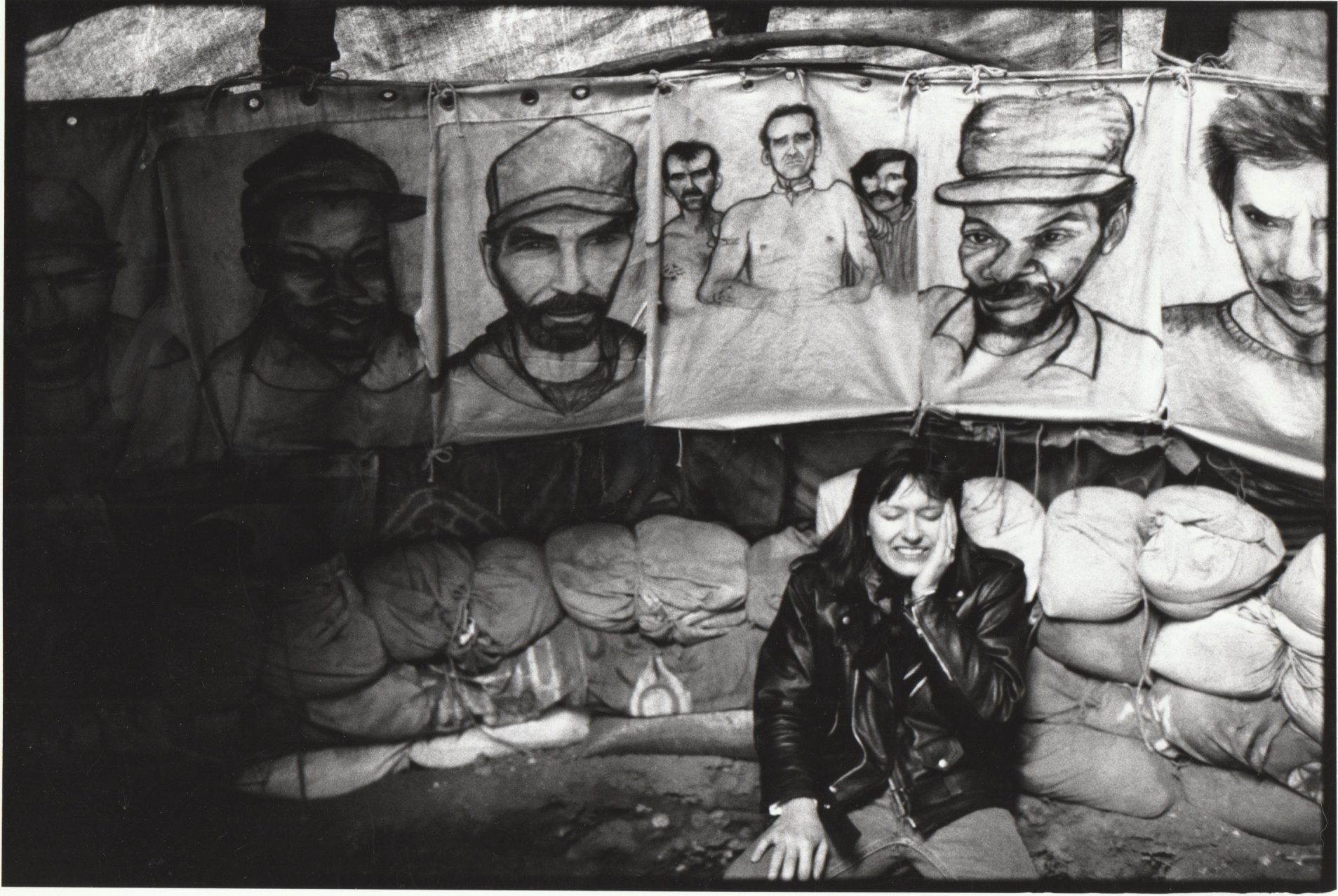

The artists grew to love their neighbors, performing theater and making art together. They sought to remove the us/them dynamic by encouraging passers-by to visit The Hill (“What’s up with the tipi?”) and get to know their fellow citizens as the funny, charming, complicated people they were. They brought marginalized people into the conversation instead of ignoring and isolating them. They dared city officials to take a stand. But mostly, they got to know their new-found friends, many of whom spent their final days of life on The Hill.

Why a tipi in a shantytown? They both represent losses – people trampled as the nation seemingly progresses. They both represent hope – people living on in the face of forces bent on making them disappear.

– Nick Fracaro

Thirty years later, during yet another pandemic, the chasm in America between the haves and have-nots — between the elite controlling the world from 52 floors up and the reality on the ground, between the neatly media-portrayed account and the actual messy world — is arguably greater and more intractable than ever. The Hill is an up-close and personal account of a temporary autonomous zone that, for better or worse, bridged the divide.

—————

The work on The Hill was extensively documented, both contemporaneously in articles (incl. The New Yorker, The New York Times, Art Forum) and over the years in museum retrospectives, books and journals. In 2020, NYU’s Fales Library offered to incorporate this archive into its permanent collection. And in 2022, the New York Public Library’s General Research Division acquired and catalogued The Hill.

For excerpts from the original hand-written journal and Nick’s serialized narrative about the same events, click here.

The Youtube video is a short trailer for the book. The Vimeo is a 3:13 minute overview of the project.

Original photo: Sy Rubin

Photo: Wendy Workman

Photo: Wendy Workman

Photo: Andreas Sterzing

Photo: Andreas Sterzing

Photo: Margaret Morton

Photo: Margaret Morton

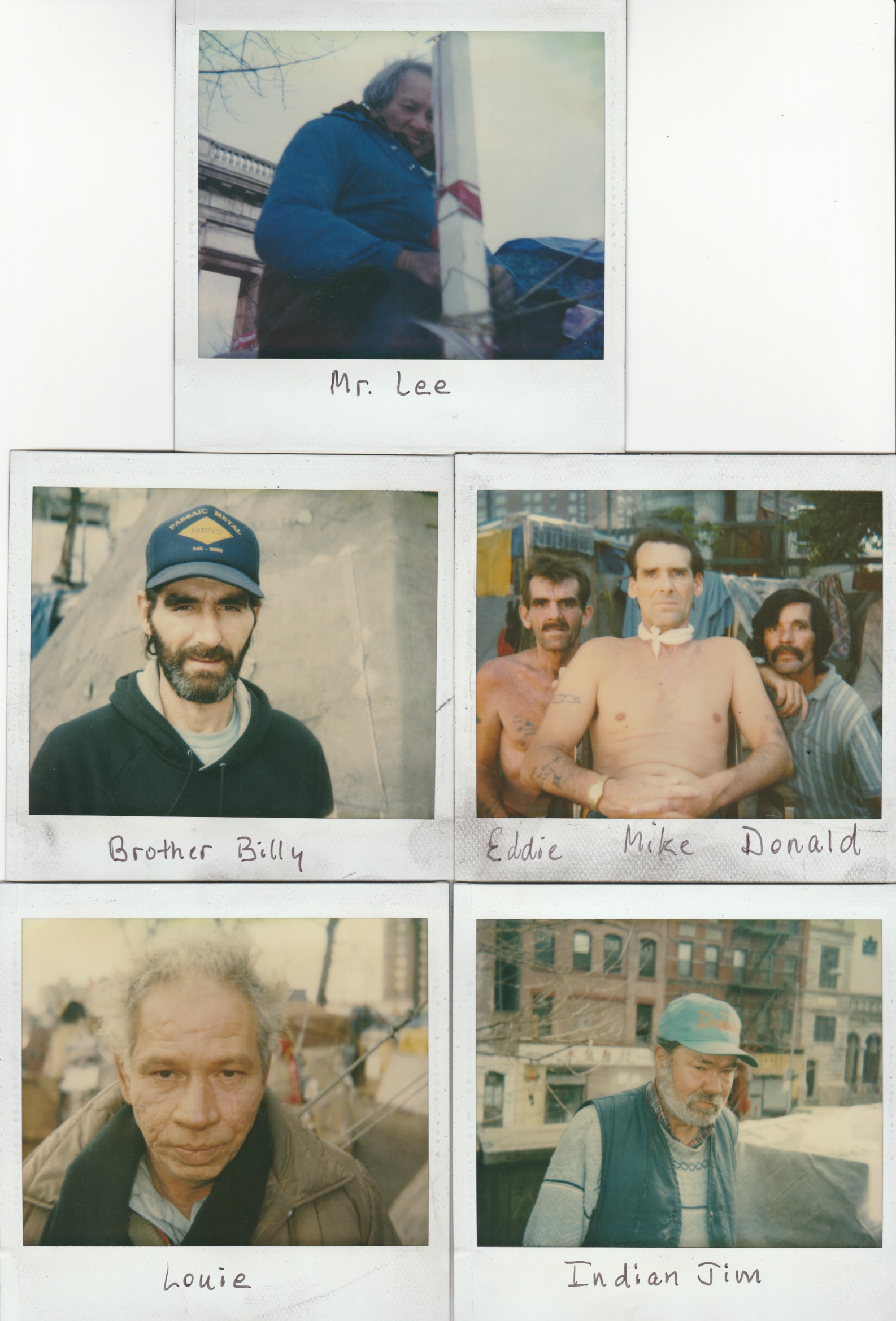

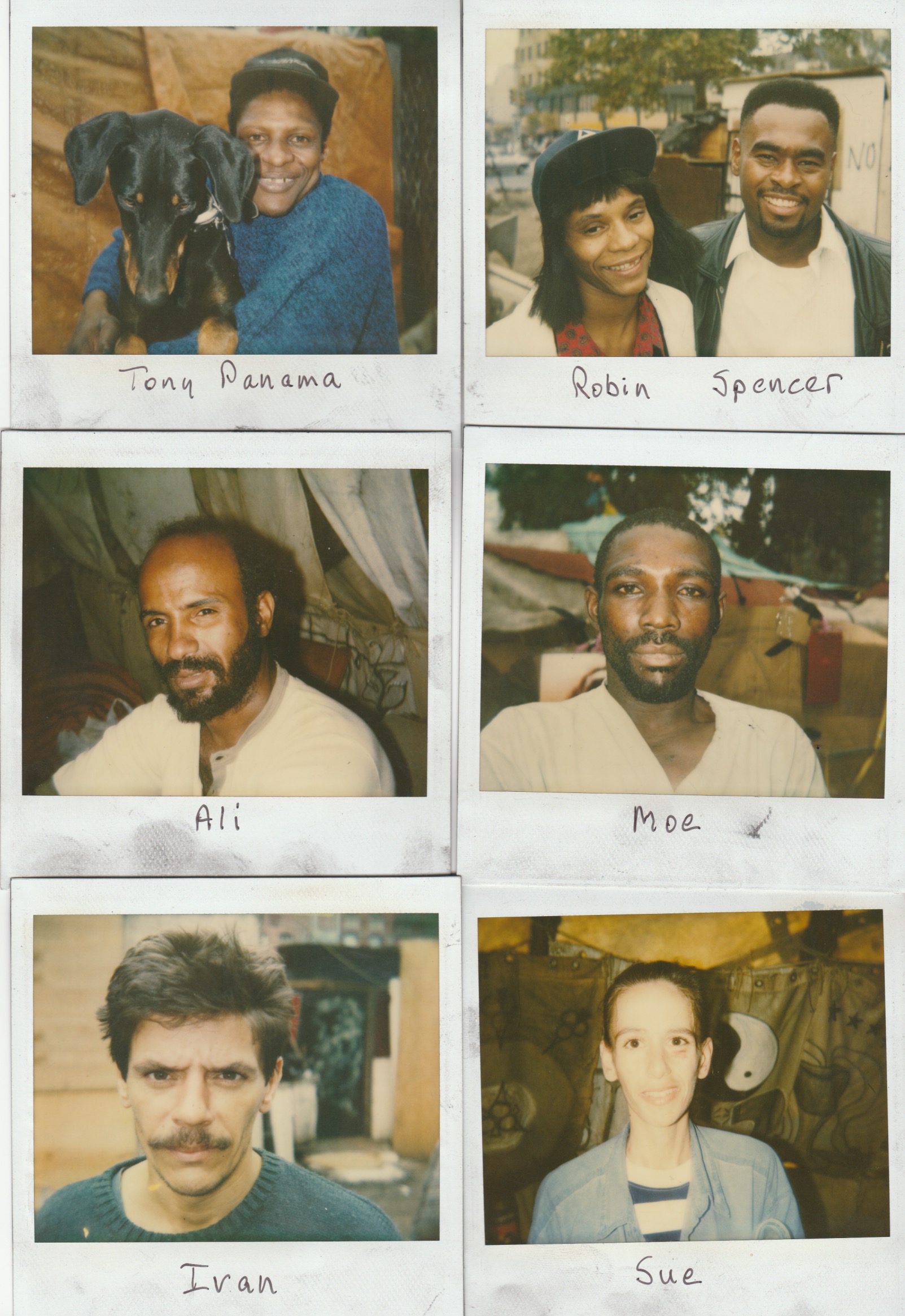

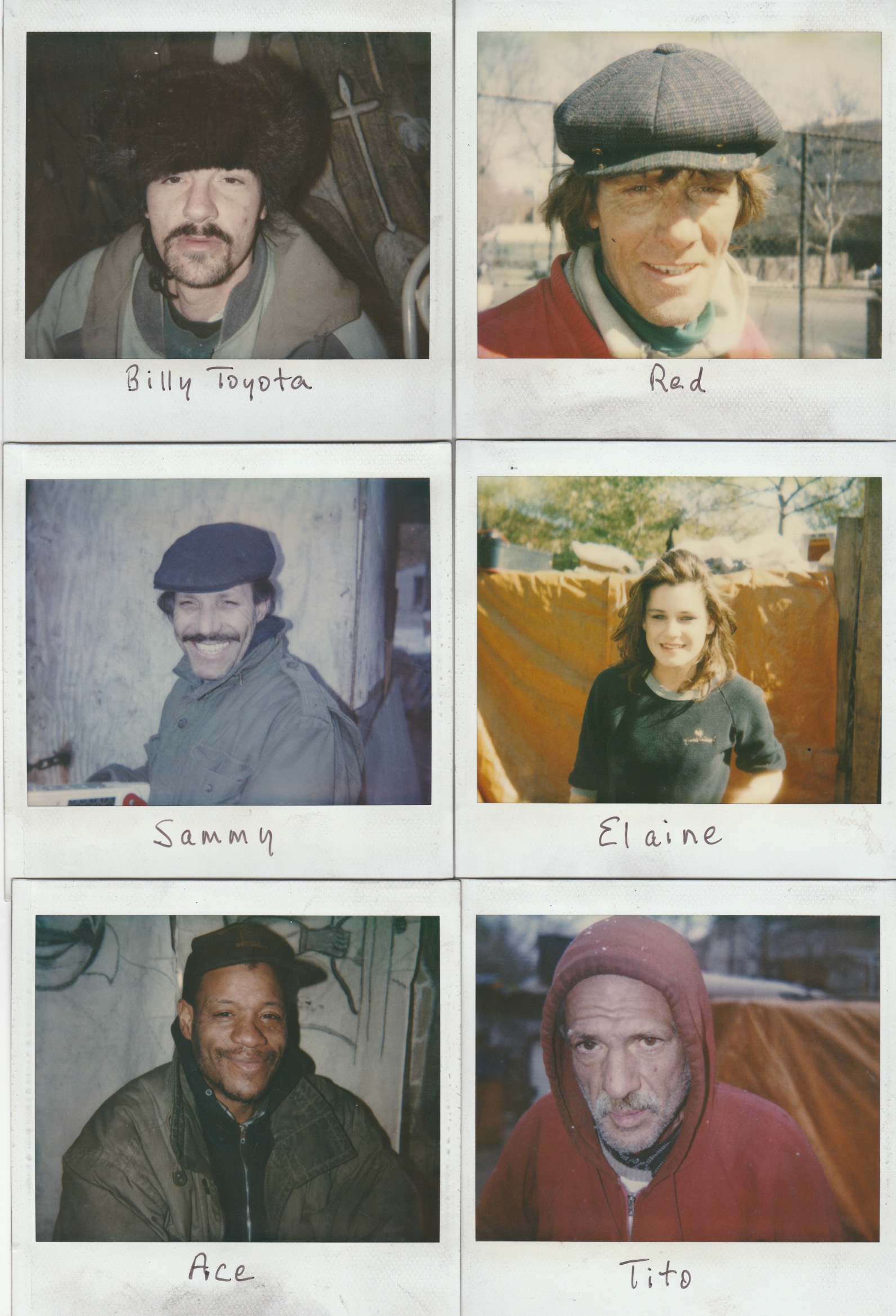

Polaroids: Gabriele Schafer

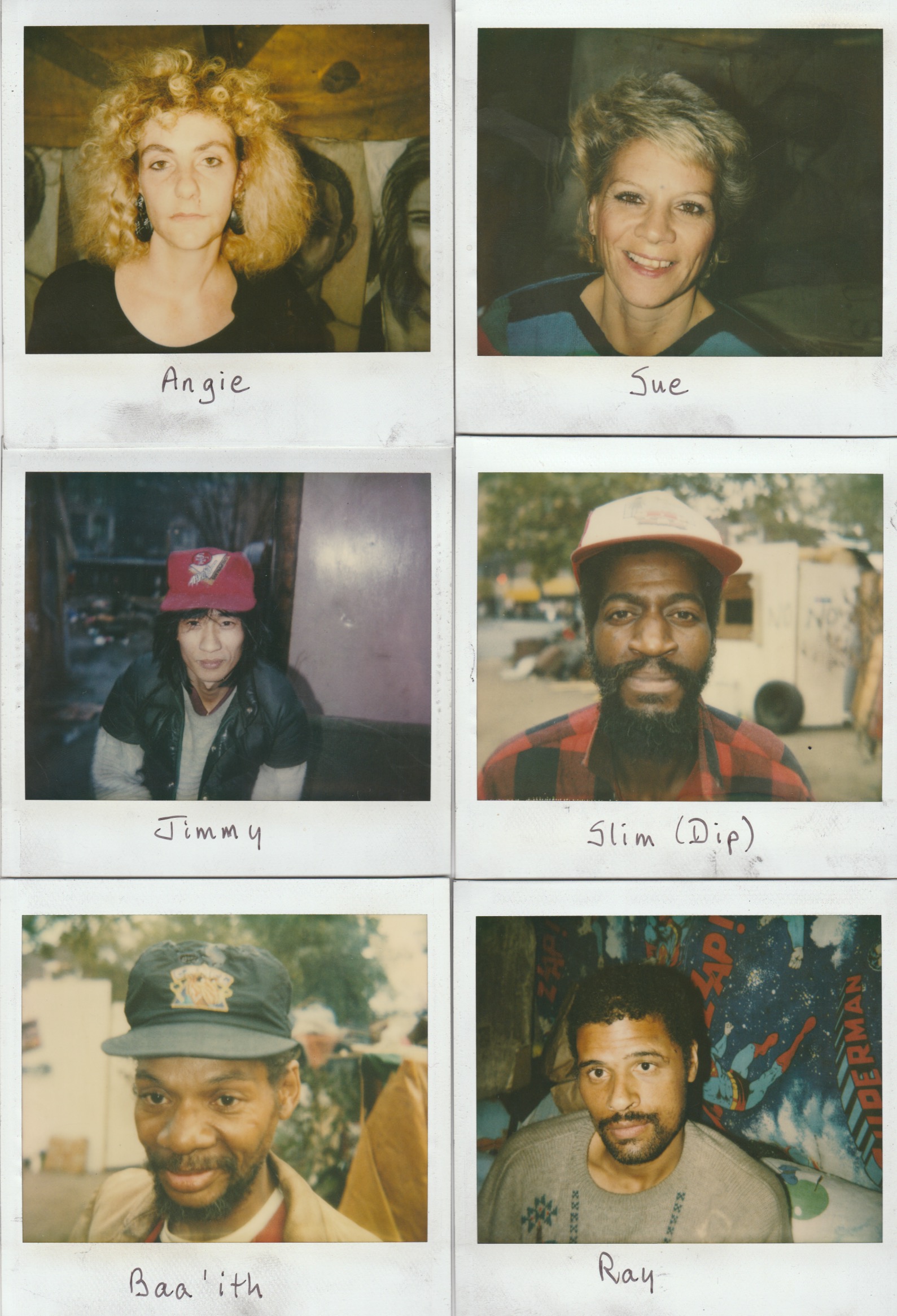

Polaroids: Gabriele Schafer