Skywalkers

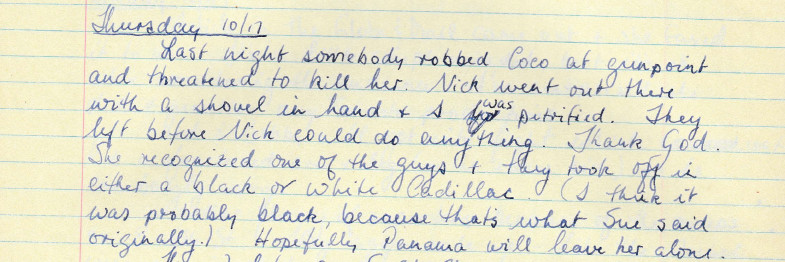

(Gabriele’s journal – October 17, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – May 19, 2022)

Any hierarchy beyond these street-level drug sales was purposefully inscrutable, not just to the police, but to the players themselves. No one knew who was who in the war zone. With all the unknowns, my only viable path toward determining what actions to take, or not take, was to lay bare the underlying metaphysics in my daily rituals and in the geomancy of the landscape.

The tipi sits directly under the monumental landmarked arch that is the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge. The top of the arch has a six-feet-high by forty-feet-long stone frieze carved into it. Titled “Buffalo Hunt,” the frieze is a depiction of four Indians on horseback with spears, bows and arrows, galloping among a herd of buffalo. Created in 1916 by Charles Ramsey, the sculpture was intended as a tribute to the Plains Indians, but it was as incongruous as the Lakota tipi in the shantytown below it. Neither belonged on the island of Manahatta, land of the Lenape, nor on the present day Manhattan landscape.

One day, standing in the yard at the spot next to the tipi where Tito had dug up the AT&T knife, I was meditating on its miraculous discovery. I looked up at the Buffalo Hunt arch. Behind and above it rose the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. I was standing on the highest hill in lower “Manahatta” gazing at the tallest buildings in Manhattan.

I already knew the history of these two man-made concrete and steel monuments because our apartment in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, was once known as “Little Caughnawaga” or “Downtown Kahnawake,” both names derived from the Mohawk’s homeland territory in Canada and upper New York State. In the 1960s, this approximately eight-square-block neighborhood had been home to about 800 Mohawk ironworkers and their relatives.

Many profit-oriented landlords in the 1930s and ‘40s had converted the four-story brownstones in the area into SROs, single room occupancy, in order to rent out their property under the same zoning laws as hotels. The brownstone we lived in had been divided into such, with twelve SRO rooms, and two common living areas and toilets, so it was likely that our apartment once housed Mohawk ironworkers and their families.

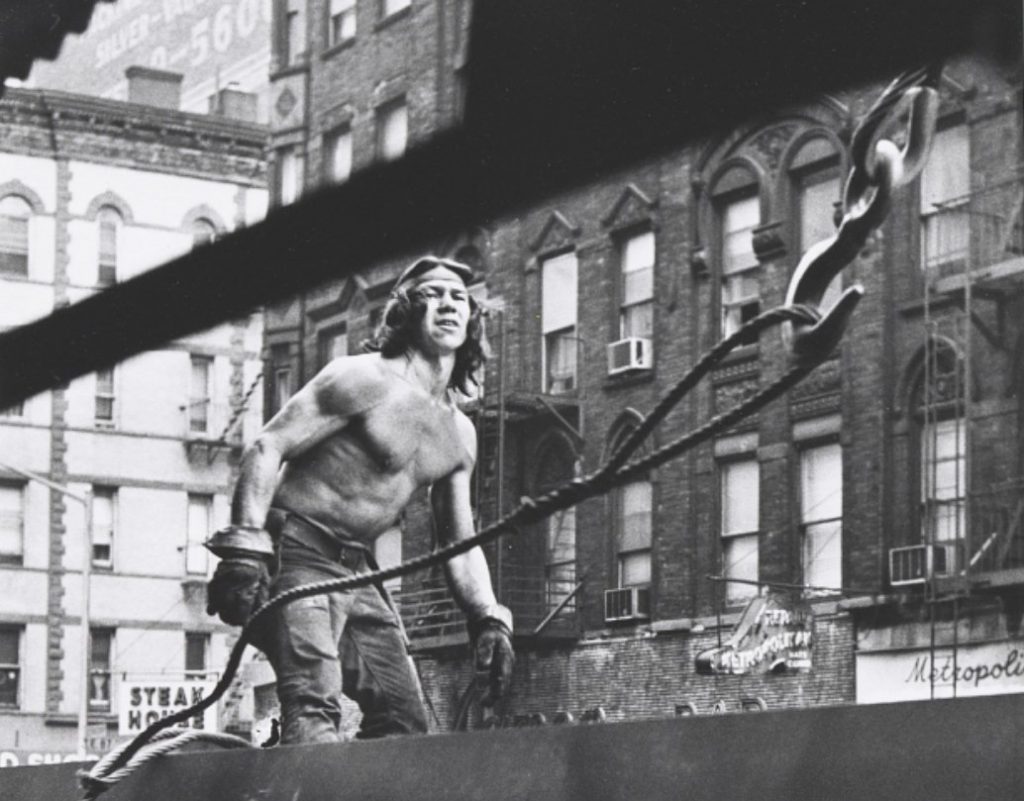

Known as “Skywalkers” for their fearlessness and skill working on the high beams of skyscrapers, Mohawks worked on the Chrysler Building in 1930, which was the tallest building in the world at the time. Less than a year later they topped that height record by helping build the Empire State Building. But the Mohawks still had two more of the world’s tallest buildings to erect.

By the late 1960s, when work on the Twin Towers began, about 500 Mohawks joined the construction crews. These fourth- and fifth-generation Skywalkers did the riveting work, which was the highest paid ironwork, but also the most dangerous. They had preserved that rare skill by having it passed on to them by their fathers and grandfathers, in the same manner as hunting, fishing, and trapping skills had once been passed down. What had started as a high-paying vocation became a tribal tradition and honored lifestyle.

The Mohawks were part of the Iroquois Confederacy that straddled Ontario, Quebec, and New York. The men had always left their villages and families for periods of time to hunt and trap the northeast woodlands, but now they left to travel to Brooklyn to live temporarily in the SROs of Downtown Kahnawake. They commuted to Manhattan each morning to “walk the iron.”

From the roof of our four-story Boerum Hill brownstone apartment building we could see clearly most of the floors of the Twin Towers. I imagined the Mohawk families twenty years earlier in 1970 on this same rooftop, and other rooftops like it in Downtown Kahnawake. They could watch daily as their men slowly erected, floor by floor, the 110 floors of the World Trade Center. Of course at this distance they would only be able to see their husband, brother, father, grandfather in their mind’s eye as they gazed at the towers. They would only be able to see the warrior spirit of the Skywalkers they loved.

On the Hill, I was standing amidst three distinct and disparate tribal references: the Lakota tipi and Plains Indian Buffalo Hunt frieze, located on the Lenape’s Manahatta island, gazing at the Twin Towers built by the Mohawks. Further, I was standing in the middle of Chinatown in the most prominent shantytown in the city.

Then it hit me and everything became crystal clear in my mind. A couple yards away Tortuga was in the pond. His spirit graced me with an epiphany, a vision that melded past and future into a timeless present.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link