Warring Landscapes

by Nick Fracaro

“I would like to stage MACBETH on top of the World Trade Center for an audience in helicopters.”

– Heiner Müller, “Hamletmachine and Other Texts for the Stage”

Thieves Theatre’s production of Heiner Müller’s Despoiled Shore Medeamaterial Landscape with Argonauts took place on two levels.

The first was a theatrical staging of the play itself, expanded upon with some of our own writing, that had eight performances over two weekends in September 1991. It took place in a New York City shantytown inside a tipi we erected as centenary memorial to the Wounded Knee Massacre.

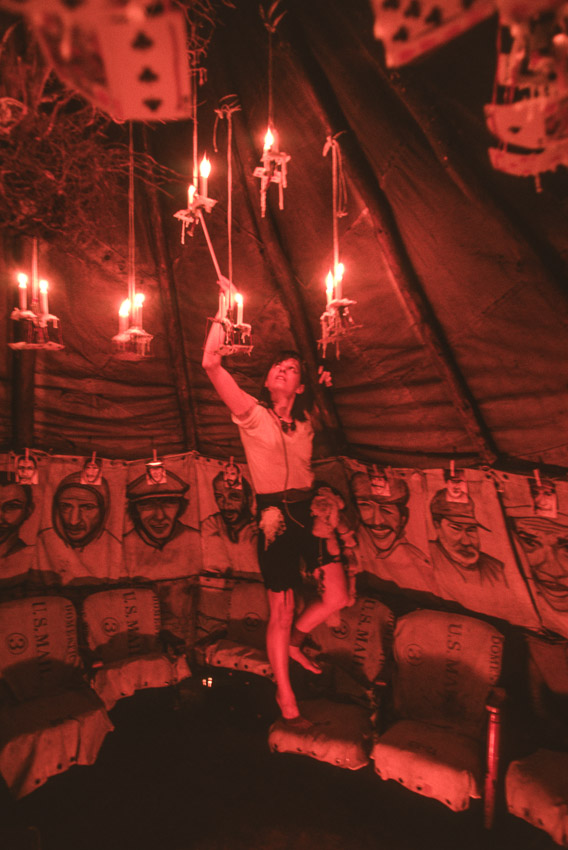

The tipi was made of 78 (the number of cards in a Tarot deck) mailbags, alluding to the canvas the U.S. Government had once given Native Americans to replace buffalo skins. It was approximately 20 feet in diameter and seated 15 people on actual theater seats found discarded on the Williamsburg bank of the East River in Brooklyn and installed around the inside perimeter of the tipi. The set consisted of pieces of ship wreckage placed in sand on the “wall” opposite of the door hole. An uprooted white pine tree was suspended upside down from the “ceiling.” In the center blazed a fire, extinguished later in the play by pouring a bucket of water into the pit and littering it with cigarette butts, condoms, and other detritus, thereby turning it into the polluted “lake” referenced in the play. Next to the fire pit was a one-foot square piece of board upon which rested a kitsch model of Manhattan; beneath it a live snapping turtle was buried in sand. The “city” was later lifted via a hoist and the turtle carried out by me. Lighting was provided by candles resting on playing cards suspended seven feet off the ground from mailbag rope attached to the tipi poles. The playing cards suggested a Tarot deck, from which ordinary cards were originally derived.

Photos: Andreas Sterzing

Photos: Andreas Sterzing

The cast consisted of Gabriele Schafer, Annie Rae Etheridge, a 13th generation descendant of Pocahontas whose story resembles the Medea tale, and me. At the end of the performance each night, I peeled off the tipi cover from the outside, leaving the audience exposed beneath the tipi’s lodge pole skeleton and the open sky, reminding them of their vulnerability within the surrounding shantytown.

The second, more arresting level of our production took place from November 1990 through May 1993 – the duration of the tipi’s existence in the shantytown – and had a significantly more expansive dramaturgy. And a much larger audience. During an average day, more than 78,000 vehicles and 350,000 people cross the Manhattan Bridge. Having left Brooklyn and waiting at the traffic light at the foot of the bridge on the Manhattan side, about to enter the financial capital of the world, this continual audience stream gazed from 30 feet away at the evolving living museum of “the tipi in the shantytown.” In all its overt and latent symbolism, this snatch of history was our three-year-long enactment and paratheatrical performance of the Müller piece.

One of our production concepts for Despoiled Shore Medeamaterial Landscape with Argonauts was inspired by Gertrude Stein: “… a landscape is such a natural arrangement for a battle-field or a play that one must write plays” (Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas). Yet Heiner Müller is not just writing plays; he is also staging battles. He brings natural history and geography into the narrative of human history suggesting that the real “theatre of operations,” the real play being written, is one of warring landscapes in which human flesh is only one element of many. The history of humankind inhabits this grand landscape/battle less as landlord than tenant – humanity as the ruling player in the drama, but only in the way dinosaurs once ruled, unable or unwilling to anticipate the awaiting tar pits of their future. As Müller queries at the end of his LANDSCAPE meditation, “Who has the better teeth, the blood or the stone?”

While the blood was busy conceiving its best-laid plans, the stone had its own subtle agenda. The tipi in the shantytown was meant, in part, to focus attention on homelessness in New York City. At the same time, in a remarkable convergence of events, some of the City’s archaeological history was about to be unearthed and incorporated into the grand mise en scene of our LANDSCAPE.

In the 1980s, urban homelessness became endemic, and America, particularly New York City, had come to recognize it officially as a problem. By mid-decade, the media were chronicling the dimensions of the condition ad infinitum, ranging from daily newspapers articles and nightly news reports to more comprehensive journalism and scholarly articles. Running on a platform that included a promise to remedy the homelessness problem, David Dinkins in 1989 became the first African American to be elected mayor of New York City.

As our new Mayor assumed office in 1990, Gabriele was building the tipi cover in the traditional Lakota dimensions by sewing together 78 opened, 2×4-foot U.S. #3 Domestic Mailbags. On a second set of 78 mailbags, she drew her interpretation of the Tarot’s Minor Arcana that served as the tipi’s inner lining. That summer we collected the seventeen pine trees we needed, each twenty or more feet in length, from a friend’s acreage in the Catskills. After a couple months of hanging out, befriending the residents, and obtaining their permission, we erected the tipi in the center of the half-acre shantytown in the darkness of early morning on Thanksgiving Day 1990, and Gabriele and I moved in.

The site was at the corner of Canal and Chrystie Streets within an elevated park plaza at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge. From this vantage point, the Twin Towers, a ten-minute walk away, stood level in height with the tipi poles on the Manhattan landscape. The area was colloquially known as “The Hill.”

The following May, a few blocks south of us, construction crews broke ground for a new federal building, uncovering what was once the five-and-a-half-acre African Burial Ground. The project would eventually unearth the remains of 427 African Americans and instigate an altercation between New York City and the Federal Government. Mayor Dinkins joined with Black community groups in demanding that the General Services Administration halt construction plans.

At this same time, two blocks to the east of the African Burial Ground, another federal construction project had initiated an archaeological excavation of a site that had once been part of the “Five Points.” Five Points was an ethnically mixed neighborhood of seminal importance to the development of New York City in the 18th and 19th centuries. Characterized as the most notorious slum in the history of New York City, its infamy impelled Charles Dickens to visit the area and to write about it in his American Notes, published in 1842. Reformers of the day described it as a squalid place of wooden shacks inhabited by thugs, criminals, drunkards, and prostitutes.

“I wanted to dig up things that had been covered by dirt and history and lies. Digging up the dead and showing them in the open. … Maybe the flesh is rotten, but they had dreams, problems, ideas that haven’t decomposed in the same way.”

– Heiner Müller, “Germania”

At the time we erected the tipi, The Hill was the oldest and most notorious of the shantytowns in the city and was characterized in the New York Post articles in the same manner as its historical antecedent Five Points. But now, with the juxtaposition of the tipi, laden with all the notions of a lost native culture and lifestyle, it had become more difficult to characterize residents of The Hill as “living like animals.” (Coincidentally, Kevin Costner’s film Dances With Wolves had premiered the same day the tipi was erected, Thanksgiving 1990. Hailed by critics and Natives alike, the movie portrayed the Lakota people honestly and sympathetically, highlighting their spiritual grace and humanity.)

Although no institution, governmental or otherwise, had authorized the tipi’s installation on what was New York State property, the project must have resembled some sort of sanctioned program because the powers-that-be never intervened. With the tipi at its center, The Hill became a tour bus stop. Teachers brought their middle school and high school students up to meet us and the other shanty dwellers. Church groups brought teenagers carrying prepared meals in exchange for the story of The Hill.

Gabriele and I told the story first. We would congregate with our neighbors and visitors inside the tipi, where Gabriele had hung her Tarot court cards, portraits of the shantytown residents lining the tipi walls. These kings and queens on The Hill enjoyed sitting around the fire within the circle of gathered images of themselves displayed as if they were a tribe. Gradually, each of them told their own version of the tale to visitors, coloring the history in their own inimitable way. Part of the original LANDSCAPE story went something like this:

In 1609, Henry Hudson reached the tip of Manhattan Island and twenty-eight canoes full of men, women, and children met him there and brought him ashore to meet their chief who welcomed and fed him. Later, Hudson returned the hospitality by inviting the chief and others on board his ship and treating them to brandy. This was the first time these Indians had encountered alcohol. They all got very drunk.

Centuries later, the Delawares still had among their traditional ceremonies an enactment of the supernatural awe they felt at the sight of the great winged vessel, the grand welcoming dance, and a garbled account of the drinking incident. They said the name Mannahattanik meant “the place where we were all drunk.” These Indians that Hudson first encountered were probably the Warpoes.

Until two hundred years ago, The Hill area was the northeast bank of a 46-acre, fresh-water pond called the Kalch-Hook, or Collect Pond. It extended west down to Centre Street and south almost to City Hall. The only historical evidence of an Indian village in southern Manhattan was found on the banks of this pond. Records show that Collect Pond was surrounded by some hills. And on one of these hills lived the Warpoes. Warpoes was either the name of the tribe, the village, or the chief. No one is sure. But it is likely that the infamous $24 sale of Manhattan was transacted with this tribe. Warpoes has been translated as meaning “little hill.”

All through Colonial times, the drinking water came from Collect Pond. But the waste from the tanning and slaughterhouse industries operating along its banks eventually polluted it. Once the water was undrinkable, the pond became a dumping place for all kinds of garbage and began to stink and fester typhus and cholera. So the city built a canal to drain it, thus the name Canal Street. They filled Kalch-Hook by using the dirt from the surrounding hills, remnants of the Warpoes. Then in 1836, the first jail in the city was built on the site. It got its name – The Tombs – from its Egyptian architecture. Later, it was torn down and rebuilt again, minus the Egyptian architecture. But it was still called The Tombs. Today, Central Booking at 100 Centre Street is being rebuilt again. But it will still be called The Tombs. If you go down to the area now you can see nearby three separate fenced-in archeological digs going on, the African Burial Ground, the notorious Five Points slum, and a Native American site…

Whoever was speaking here might have colored this section of the LANDSCAPE story with their own experiences at the Tombs. Most of these storytellers had been “put through the system” of Central Booking more than once. And for all the residents, the literal tombs lurked just as near as the jailhouse Tombs. Violence in both its overt and subtle forms was a constant presence on The Hill. Ambitious, aggressive drug dealers, each with their own posse, warred with one another over who would be most feared and control the trade.

But none could match the posse of diseases and the grim efficiency with which they kept the population in flux.

Emergency Medical Technicians wouldn’t enter the shantytown. The sick or wounded had to be carried to parked ambulances on the street. A multiple-drug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis had become epidemic in New York City in the early 90’s. Spread in tiny droplets through the air, TB is most potent in such places as unventilated shanties or homeless shelters. But mostly those living with HIV/AIDS and its complications spent their last days of life on The Hill.

In August 1993, bulldozers pushed The Hill and its story into some Collect Pond of memory. And I understand it more as destiny than coincidence that on September 11, all of the archeological artifacts from Five Points and the African Burial Ground were stored at the World Trade Center. The Twin Towers were both the actual and symbolic backdrop of the “tipi in the shantytown.” Polar opposites and phantom icons of the battlefield that was, and is, Collect Pond.

At what point do neighbors become friends, do friends become family? Although all the kings and queens of The Hill are gone, I still meet them now and then in some LANDSCAPE we will forever share. I look back now on the haunting prophecy of our eternity.

The Southern wind toyed with old posters

OR THE HAPLESS LANDING The dead negroes

Rammed into the swamp like poles

In the uniforms of their enemies

DO YOU REMEMBER DO YOU NO I DON’T*

The dried up blood

Is smoking in the sun

The theatre of my death

Had opened as I stood between the mountains

In the circle of dead comrades on the stone

And the expected airplane appeared above me

Without thinking I knew

This engine was

What my grandmothers used to call God

The airblast swept the corpses off the plateau

And shots crackled at my reeling flight

I felt MY blood come out of MY veins

And turn MY body into the landscape of

MY death

IN THE BACK THE SWINE

The rest is poetry Who has the better teeth

The blood or the stone

*English in the original.

(Translation by Carl Weber)