A Visit from the American Indian Movement

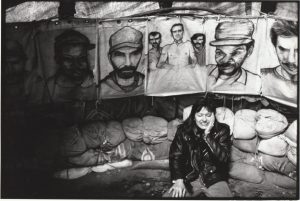

Photo: Wendy Workman

Photo: Wendy Workman

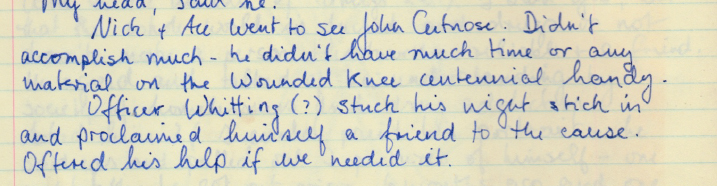

(Gabriele’s journal – December 4, 1990)

(Nick’s narrative – January 6, 2022)

We never expected the powers-that-be to allow the tipi to stand for more than a day, but before erecting it, we had reached out to representatives of the local American Indian community. We ended up speaking to John Cutnose of the American Indian Community House about our intentions. That December 29th would be the centenary of the Wounded Knee Massacre, and now that the tipi was still standing, we spoke to him again about helping to locate anyone who might want to participate in the dedication ceremony we had planned.

We had studied extensively the Paiute prophet Wovoka and the Ghost Dance phenomenon that had united many American Indian tribes a hundred years earlier. During the solar eclipse on January 1, 1889, Wovoka had a vision of dying, going to heaven and being told by God to teach the Ghost Dance. He had been influenced by the Indian Shaker Church, founded a few years earlier, which was a unique blend of American Indian, Catholic, and Protestant beliefs practiced at the time. With the tribes banding together across different cultures and geographies, and with few being able to speak Wovoka’s mother tongue of Paiute, a militant form of the prophecy had developed. With emphasis placed on an impending great battle, the Ghost Dancers created Ghost Shirts, whose spiritual power was believed to make their wearers impervious to bullets.

No one contacted us before our dedication ceremony, but a few days afterwards, a man and woman appeared at the tipi identifying themselves as members of AIM (American Indian Movement). I had read about the group’s protests and actions, so I knew them as the most prominent militant American Indian organization. Somewhat uneasily I invited them inside and offered them seats on our bedding. They each sat on the ground, so I did the same. They both looked around intently, especially at the lining of opened mailbag rectangles that Gabriele had painted with oil sticks. She had begun her portraits of our neighbors, so several of these portrait canvases were now part of the lining, scattered among her illustrations of the Minor Arcana.

“You’re Nick Manhattan?”

The New York Post photo of me and the article that came out the day after the tipi was erected had been hounding me for weeks. The Post’s photographer had captured an image of me with my arms crossed in front of my chest and the headline read “He’ll take Manhattan.” Gabriele and I had wanted to remain as anonymous as possible, so I had created the pseudonym Nick Manhattan on the spot in response to the reporter’s inquiry. Eighty-thousand cars and trucks used the Manhattan Bridge daily. The down ramp on the Manhattan side had a stoplight right at the shantytown entrance. For weeks after this Post article, passengers in those cars would yell “Hey Nick Manhattan” from their windows when they saw me standing out in the open.

“No. That’s not my name. I made that up for a reporter. I don’t want people to know my real name. But the Nick part is real. I’m Nick.”

“When I asked for you, one guy out there said, ‘You mean, Chief. He’s inside.’”

“Yeah, Chief, that’s kind of a joke name that stuck, a nickname that many here often call me.”

“I’m Chayton and this is Mika. Did you build this?”

“Mostly my wife. She sewed the cover together.”

“Is your wife Indian?”

“No. She’s German.”

Chayton smiled faintly. “How did a German learn how to build a Lakota tipi?”

“She used a book.”

“I think I know the book. The authors are the Laubins, right?”

“Yeah, I think that’s their name.”

“My friends used that book when they built their tipi upstate. Where did you get those lodge poles from? We had a hard time finding the right size anywhere. We eventually found the right ones in a burnt-down pine section on a Jersey Turnpike median.”

“Upstate near Woodstock. Friends own about fifty acres of forested land and allowed us to harvest them. These poles were in three or four different thick pine groves. There wasn’t enough light for the pines to grow full size. They grew only to this height and then died standing upright. We tied them to my van’s roof and drove them down here to the City.”

Mika had been scrutinizing the inner lining of the tipi. “The designs drawn on the canvas are not Lakota. What are they?”

“My wife drew them. It’s her interpretation of the Tarot.”

“The Tarot? Some kind of witchcraft?”

“No. It’s not witchcraft.”

Chayton stood up quickly and walked closer to the canvas lining. I rose with him. I had suspected from the start that this was not just a “hello” kind of visit from AIM but one more on the order of an investigation, an interrogation of the tipi and its owners. Although we had received tentative support from John Cutnose prior to erecting the tipi, after it was up and we were living in it, Gabriele had received a disturbing phone call from a person named Steve King.

Through media reports, the Hill had a reputation for drug and alcohol abuse which was in large part accurate. Except for Mr. Lee, the Chinese geomancer, and ourselves, everyone on the Hill was an addict, alcoholic, or at the minimum, prone to drug and alcohol abuse. Nevertheless, without exception, the residents instantly understood the tipi as something to be held in awe and reverence. They believed a church, their Church, had been built at the center of their community. They met inside when they wanted some quiet and sought to share the vulnerable sides of themselves, the sides that were largely at odds with their rough-edged, day-to-day lives defined by hustling and theft to support their habits. Mostly they sought out Gabriele. “Mrs. Chief” became their confessor. Individually, they came into the tipi to sit awhile and share their life stories with her, which then informed the portraits she drew of them.

Chayton was inspecting closely the three of hearts that Gabriele had interpreted on one of the canvases. “Tarot? You mean the card deck, right?”

“Yes. But it’s become more than just that for us. That’s the three of hearts, the three of cups in Tarot, you’re looking at now.”

“Do you know anything about the American Indian Movement?”

“Just what I have read. Never met anyone involved in it until you.”

“What have you read?”

“I’ve read about your occupations of Alcatraz, Wounded Knee, and the Black Hills. Very righteous acts in my mind, standing up for past and present crimes against Indians. We built the tipi and erected it here on the Hill in solidarity with that. We dedicated it on December 29th, the centenary of the Wounded Knee Massacre, as a memorial.”

“Why here? The people living here are all drug addicts and alcoholics.”

“For the most part, yes. They still deserve civil rights and some basic dignity. And they all have complete respect for the tipi. It almost instantly became like a church to them. And of course, never any drugs or alcohol are allowed inside. No one even enters it unless Gabriele or I are here. That’s enforced by everyone living up here. Everyone participated in the dedication ceremony.”

“Were there any natives at the dedication?”

“Maybe, I’m not sure. There were only a few people I didn’t know who didn’t introduce themselves. We had reached out in the months prior, before the tipi was even erected, to John Cutnose at the American Indian Community House. He seemed supportive, but then sometime in December, he had someone named John King call us. King just assumed we were having wild parties with drugs and alcohol inside the tipi. He never bothered to listen or get to know us and told Gabriele that there was no value in the commemoration if Indians were not involved. He then threatened to come by with a hundred Indians and tear the tipi down and hung up. She immediately called John Cutnose and told him to call his friend and tell him we changed our mind, that the tipi was our home now, our sacred space, and that the likes of John King weren’t welcome here. That if he represented the larger local Indian community, we would do the commemoration ourselves. We would humbly appeal directly to the Ghost Dance warriors and others who died at Wounded Knee to accept our memorial.”

“You should know, if this tipi were being disrespected, as John King said, AIM would bring a hundred Indians to tear it down.”

Chayton put this statement to me as a challenge, a thinly veiled threat. I decided that what I said next should be my final words.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link.