Five Points

(Gabriele’s journal – January 21, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – May 5, 2022)

When I found the story of the ragman hermit, I xeroxed the page from the reference book, another talisman to be added to my medicine bag. The city had been recently clearing homeless encampments, but I knew now the Hill was beyond its jurisdiction, belonging to a greater domain. The spirit of the ragman and hermit was its protector. The enigmatic soil of the Hill was a site for the eternal recurrence of history, and I saw the personification of that spirit in the two odd men out on the Hill: The Chinese geomancer was the Hermit living in his underground hermitage. Mister Lee was the Ragman living in his tied-together patchwork hut.

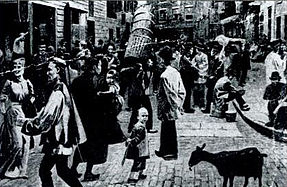

After the landfill of the pond was completed in 1811, high-end houses were built there for the upper and middle classes. The development was dubbed “Paradise Square,” but the landfill had been shoddily engineered and the ground had remained naturally a lowland, lacking any sewage drainage. As a result, all the houses began to shift in their foundations and started crumbling. The buried vegetation released methane gas. The unpaved streets were often buried in mud mixed with human and animal excrement. Mosquitoes bred in the stagnant pools created by the poor drainage. Paradise Square was definitely no paradise, and by 1820 the middle- and upper-class inhabitants had fled, leaving the neighborhood open for the always steady stream of poor immigrants. The five-pronged intersection which lay at the center of this would-be paradise served as its new name, Five Points.

The poorest of immigrants to America of every ethnicity moved to the Five Points district. That immigration peaked in the 1840’s when Irish Catholics who fled the Irish Potato Famine settled there. The overpopulation, disease, infant and child deaths, unemployment, illegal saloons, gambling, prostitution, and violent crime was unequaled in the Western World at that time.

The original gangs of New York were formed here and they made Five Points one of the deadliest places on earth. Legend had it that the tenement called the Old Brewery saw at least one murder every night for 15 years. For nearly a hundred years, various gangs from Five Points essentially ran the city. Corrupt police, politicians, and gang leaders were one hand washing the other.

The flipside to the destitution and violence of Five Points was that it has also been touted as the original American melting pot. The first residents were poor Jewish, Italian, and Irish immigrants, and with the end of slavery in New York in 1827, newly emancipated blacks moved in. This cohabitation was the first instance of voluntary large-scale racial and ethnic integration.

Five Points was rich in historical data, but it was easy to see how the narratives about that period were a hybrid of fact and fiction. From the 19th century to the present, novelists and newspaper reporters, from Charles Dickens to Nathaniel Parker Willis to Luc Sante’s new book, Low Life, have made Five Points the symbol of all that was dark and dirty in the early city. Doubtless, there was more to life than the vast inventory of evils that was the sole focus of generation after generation of writers. Their accounts shared the same biases. They were all searching for a past more sordid than their present day. Likewise, at the other end of the spectrum were narratives from writers eulogizing the “melting pot,” while understating the constant racial and ethnic tension and numerous flare-ups of violence.

The truth about what life was really like was probably somewhere in the gray area between the two extremes. I took Five Points as both the literal and figurative soil that seeded the current era. Only the names and ethnicities had changed. The Irish Dead Rabbits, Bowery Boys, Plug Uglies of the 19th century were mirrored in news reports on contemporary local gangs – the Chinese Flying Dragons, Ghost Shadows, and the Vietnamese Born to Kill. The corrupt cops of the Five Points had their counterpoint in the Fifth Police Precinct’s Frick and Frack Fury in the current Chinatown.

From Blade’s story to the Hill thieves and addicts’ interactions with corrupt police, gangs, fences, and drug dealers, history was in a repeating cycle for those living in the criminal subculture. Unknown was to what degree that subculture was in partnership with government entities. Even if the city’s governance bore only a glancing resemblance to the notorious Tammany Hall of the Five Points era, my already quixotic notion of finding the evidence to bring the White Boy gang to courtroom justice would likely not only be foolish, but deadly.

The prosecutor and judge at my arraignment seemed honest brokers of justice, but they would have dealt only with the surface level of crime in the world of the White Boy gang. Still, they knew more than me. Most surprisingly, they had referenced the “crack smile,” which is central to my investigation, by name.

I knew a little something about the street level politics of crime in Chinatown but nothing about the various higher levels of community and government authorities necessary to sanction that crime.

My avocation, long before moving to the Hill, was research into the history of the native cultures of America. Now living on the Hill, that inquiry had dovetailed, and become more specific and more obsessive. I needed evidence. Evidence of the crimes of the White Boy gang, but more importantly, the mounting evidence for me of the historical synchronicity affirming the existence of the Mouth of the Dragon. So I combed through the history of Chinatown for clues and proof.

First clue, the current and historical presence of the Chinese tongs are central to the governance of the neighborhood. When disputes arise, people are more likely to turn to the tongs than to the police to resolve things. A tradition partially inherited from mainland China, the secret tongs have ruled, and protected, the Chinatown populace since its beginning.

The Chinese arrived on the west coast of America in large numbers in the 1840s and 50s as part of the gold rush and the labor market that developed around the building of the Central Pacific Railroad. When the gold mines began yielding less and the railroad neared completion, the Chinese moved east into the larger cities, where employment opportunities were more plentiful and they could blend into the already diverse populations. Five Points was one such destination.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link