Ma Bell

(Gabriele’s journal – January 23, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – April 14, 2022)

Everyone recognizes that Tito will die soon if he goes untreated. They also know that they, too, will face the same Wolf sooner rather than later. Life on the Hill with its manifest and latent violence, its diseases, is a community of the immune compromised. The best, if not only, defense is denial.

When the wolf is at the door, it’s best not to open it and face reality. Just go on living one more day. “He wants to go out this way. It’s his choice.” In his role as sacrificial Lamb, Tito receives limited but palpable homage for his stoicism.

But the Lamb is unsure of his choice. He asks Gabriele if she can get some antibiotics from her doctor. Gabriele explains to her doctor the situation and he agrees to help, but Tito doesn’t follow through with the necessary phone call to him. He asks me for a ride to the hospital one morning. He returns to the Hill that evening, “They wanted to put a bag on my side for my piss. I ain’t gonna walk around with that.”

Often after getting high, Tito and the other addicts stepped out of the huts and methodically began searching the yard. The high had triggered the notion in their heads that they’d dropped or lost something.

One day Tito was fastidiously studying the ground. He looked like he had stepped out of one of those old Westerns on TV. He was the scout, the skilled tracker discerning in the tramples and disruptions in the landscape a direction for the pursuit. Amused and curious, I walked up next to him, trying to see what he was seeing.

“What you looking for?”

“You’ll see.” Tito pulls out one of his cherished spark plugs from his pocket and uses the tip to begin digging in the ground. A couple minutes later he excavates his prize. It’s a pocket knife with a AT&T logo on it. I’m amazed and confused by his discovery.

“What? Had you buried it there?”

“No, I found it. I didn’t know what it was, but I knew it was there.”

“That’s crazy.”

“Not crazy. You just gotta listen and see what’s going on. I find a lot of things. You wouldn’t believe.” Tito starts to put the knife and spark plug into his pocket but stops, offering me the small jackknife. “You want it. It’s special.”

It was special, a miraculous discovery in my mind. I reached into my left pocket and pulled out the Canal Street knife, “I’ll trade you.”

“I don’t want to take that away from you. Anyway, I owe you for all the change you give me.”

I put the AT&T knife into my pocket. It would replace the Canal Street knife which had replaced the lost Buck Knife. It’s small three-inch blade made it ineffective as a weapon, but this “Ma Bell” artifact now shared exclusive space with my Motorola telephone pager. My left pocket was Communications Central, keeping me receptive to alerts – Motorola fielded my day job business and Ma Bell kept my instincts keen.

The pager at that time was the preferred communication device between drug dealers and their street runners. When we arrived on the Hill, there was no selling of drugs there, no drug dealers, so I was the only one with a beeper. The mutually agreed-on ban stemmed from the belief that selling drugs would be the exact reason authorities needed to raze the shantytown.

With my pager service I could work my day job more or less remotely. I ran a one-man Queens warehouse/office for Pacific Studios, a Los Angeles-based business that produced and rented large photographic backdrops for the film and television industry. The warehouse had a stock of about 100 backdrops that were primarily rented to the television shows produced in New York. If Gabriele or I were not at the office to answer a call, the answering machine paged me. I retrieved the message immediately and returned the call.

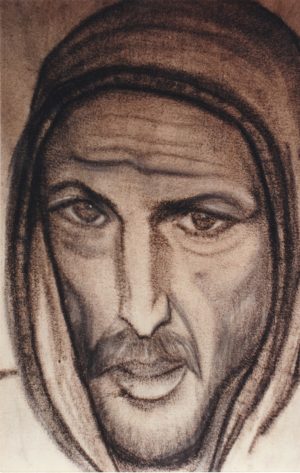

Although I was technically the sole paid employee, for the most part Gabriele worked this non taxing job, which then allowed me to be on the Hill every day. The warehouse also gave Gabriele the space and time to set up the sewing machine and then to lay out, design, and create the teepee cover. After the tipi was erected, the warehouse became her studio where she drew her Tarot card illustrations and portraits for the inner lining. From the office she managed the “business” of our tipi project and documented it day to day in her journal.

After a day at Pacific Studios, she sometimes changed clothes and went straight to her corporate day job at Rothschild. She worked evenings as a secretary for a Wall Street tycoon known in the press as the “bankruptcy king.” The job gave her a limo ride home at 10pm, which meant that she often had to convince the black car driver that, yes, she did indeed want to be dropped off at the shantytown at the corner of Chrystie and Canal Streets.

Pacific Studios and Rothchild not only allowed us to be on the Hill as much as we wanted, but also to pay rent on our Brooklyn apartment, so unlike most of our neighbors, we always had a shower and change of clothes. The apartment at first was a refuge, providing brief escapes back into our previous lifestyle, but we became as addicted to the Hill as the others. Except for the day jobs, one or both of us spent day and night on the Hill, and the behaviors, routines, and ethos of our old life soon evaporated. We belonged to the Hill and the Hill belonged to us.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link