Requiem

(Gabriele’s journal – March 16, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – April 7, 2022)

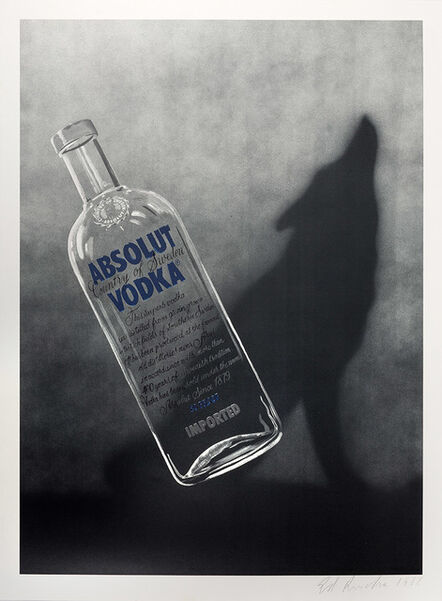

After Gabriele leaves, I sometimes make another cup of cowboy coffee for Tito and me. Partially his age, but mostly because of his demeanor, I admire him more than the others. He is soft-spoken and unassuming. The year prior to moving to the Hill, he had been the top waiter at Sammy’s, the famous Roumanian steakhouse just a few blocks up Chrystie Street, north of Delancey. He had worked there for almost ten years. He described to me how he placed bottles of Absolut Vodka in empty half-gallon milk cartons filled with water in the large freezer. Once the carton was cut off, the Absolut bottle sat beautifully framed in a clear block of ice. Gripped in a white towel, he carried the ice block bottle of vodka to the customer’s table to pour shots.

“I invented that gimmick. The customers loved it. So did the owner. So he always had me serve the vodka. Every table. I got a percentage of the tips from the other waiters, depending on how much vodka I served. What the customers didn’t know was that the owner had me refill and recap the bottles with cheap Smirnoff, not Absolut.”

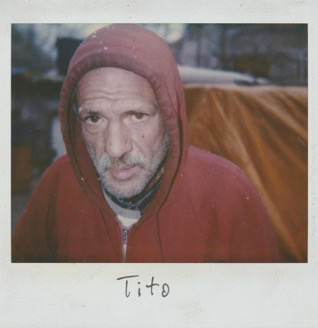

Tito had worked as a waiter and bartender most of his life. The stories about his various jobs and interactions with different celebrities were interlaced with present-day stories of his life as a thief.

“Let me show you how I do this.” Tito pulls a car spark plug from his pocket. “See this. This is like gold to me. Let me borrow your hatchet over there.”

He positions the spark plug against one of the large rocks around the firepit. Holding it with the index finger and thumb of his left hand, he raises the hammer end of the hatchet with his right to strike, but stops.

“I better not do this. I could fuck up here. Better to do it the normal way. What I do is shatter the spark plug on the sidewalk using a big rock or brick and then pick up all the little pieces of white. I don’t know what it’s made of, but it must be harder than most other stuff, because it’s the only thing that I’ve found that works. When you break into a car or van, you don’t want to make noise shattering a window. So you stand back a couple feet with these white spark plug pieces in your hand and throw them as hard as you can at the vent window. The window will shatter making no noise at all. Then you can reach in and unlock the door through the vent.”

Tito relates these stories of his life with a restrained pride, in the same manner that I imagine he had served his ice block vodka to the restaurant patrons in his former life. And as with any such formal service rendered, a gratuity is expected. “You got any spare change?” I am prepared for the ritualistic exchange, always having the dollar or so in change in my right pocket. “How much do you owe me now, Tito?” Not a question with a real answer, just part of our morning liturgy.

The daily conversation and goodbye with Tito feels as solemn as a Catholic Requiem Mass. When my brother and I became altar boys, the Church had just begun translating the liturgy of the Mass into English, so we had to memorize both the Latin and English responses. At the Funeral Mass we sang our responses to the Priest in Latin. I only remembered one Latin response from back then. I pronounced it out loud to Tito’s portrait after he left each morning, phonetically, the way I memorized it, “Et kome spirit tutu aaah.” I had forgotten what it meant in English but it felt like the right blessing to a spirit I admired for its resolved necessity to carry on.

The humiliation of his physical condition is as much a torment as the pain. “I can’t piss like a man anymore. I got to squat like a woman. It comes out everywhere down there.” Tito’s walk is measured, the pain in his steps obvious. He moves out into his life each morning much like a wounded animal might, except he is conscious of his impending death, as is everyone on the Hill. We all watch and discuss his journey, offering him possible exit ramps, but he has taken on the role of the sacrificial Lamb.

The Thief, The Wolf, The Lamb. They all are elements in each of us, but the big bad Wolf is the one lurking in the shadows as disease. Emergency Medical Technicians won’t enter the Hill. They know most living here are heroin addicts who have HIV/AIDS from shared needles and that the multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR) has become epidemic in the City. Spread in tiny droplets through the air, it is most potent in places like the Hill’s unventilated shanties and the homeless shelters. The sick or wounded at the Hill need to be carried to parked EMT ambulances on the street.

Everyone recognizes that Tito will die soon if he goes untreated. They also know that they, too, will face the same Wolf sooner, rather than later. Life on the Hill with its manifest and latent violence, its diseases, is a community of the immune compromised. The best, if not only, defense is denial.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link