The Trinity

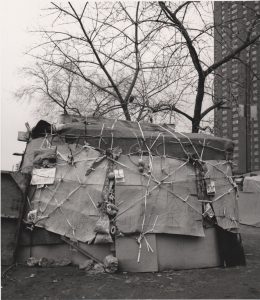

Photo: Margaret Morton

Photo: Margaret Morton

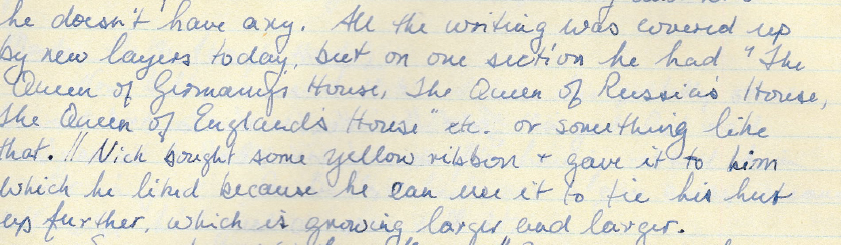

(Gabriele’s journal – February 9, 1991)

(Nick’s narrative – December 23, 2021)

Mister Lee claimed that the inside consisted of many rooms, including one for the Queen of China, the Queen of Germany and the Queen of Russia. His scrawled placard over the door read “House of the United Nations.” Everyone of course chuckled at his incredible claims. I, alone perhaps, believed them as true, or at least as true as my own visions … hallucinations. Reality has many layers with permeable borders. Revelations to the self at reality’s borders most often read to our clinical modern world as psychic delusions. What realm of truth and vision existed in Mister Lee’s House of the United Nations? And what valuable object at the “Crazy Door” was he now about to pull out of his gray canvas bag?

Mister Lee pulled out an approximately two-foot square piece of paper and unrolled it against the Crazy Door, positioning and holding it in place so that it covered the area of the White Boy tag. The image on the glossy paper was the life-sized face of a female model, probably torn from some larger product advertisement. He held the face up to me, “La Reina de Africa tiene problemas.” He pointed to the White Boy tag and mimed it over the face of his Queen of Africa. Then, with his right hand holding an imaginary brush, he mimed the movement of the White Boy tag larger than life in the open air. “Muerte.”

Mister Lee was distressed now, returning to the Crazy Door and picking up where he left off minutes earlier. He was talking to someone he loved. Someone beyond the graffitied wall, the Queen perhaps, someone that I, and the many other passersby on this Chinatown sidewalk, could not see or even imagine.

I backed away down the sidewalk about ten yards. I felt I needed to give Mister Lee some privacy but I also wanted to stay close. He had confided in me and introduced me to whoever he saw at his Crazy Door.

I watched as people walked by him, giving him as much berth as the sidewalk would allow, but also curious about his plight, often turning back to stare at him after they passed. Most of the passersby were Chinese, so some probably understood what he was saying, though Mister Lee spoke Cantonese, whereas most residents of Chinatown spoke Mandarin.

I wished I had the language, but maybe I understood enough. Or maybe I understood too much. Not just about Mister Lee but also about myself. Crazy Door was no longer solely Mister Lee’s quandary. It was now also becoming mine. The tarot archetype The Fool had begun speaking to me unfiltered. He would become my mentor.

After about fifteen minutes, Mister Lee stopped talking and just stood staring at the wall. A few minutes after that he walked away. I called out to him, “Mister Lee. Voy a ver Tortuga.” He smiled and lifted his right arm in acknowledgement, reached into his bag, pulled out some type of Chinese greens and offered them to me. “Comida de Tortuga.” I headed back to the shantytown with the turtle’s lunch while Mister Lee continued on his day’s journey.

In water tanks attached to their semi-trailer bed, an Arkansas trucker couple weekly delivered live carp, frogs, and turtles to the Chinatown restaurants and vendors. They had visited the tipi a couple weeks after we moved in, and in conversation I told them about the creation story of the Native American Lenape, how they believed their homeland was created when the Great Spirit placed the earth on the back of a giant turtle. The trucker couple offered to bring me a snapping turtle from Arkansas, so by the time they returned the next week, I had already built a fenced-in pond in the shantytown. With siphoned electricity from a city streetlight, I had hooked up a large aerator to oxygenate the water.

Mister Lee’s House of the United Nations was right next to the tipi, so the new turtle pond was midway between us. Most mornings, just after sunrise, we stood at the pond to have simple but animated conversations about Tortuga. One continuing argument was “Tortuga belongs to the sun.” “No, no, Tortuga belongs to the moon.“

For the most part, I was the only one who talked with Mister Lee, except for Sammy, the builder and owner of the largest residence on the Hill. He sometimes instigated an argument with Mister Lee over the size of the House of the United Nations. They were mostly sham disputes. Sammy had painted lettering on the side of his residence: “La Ponderosa.” The structure was at least three times as large as the House of the United Nations, so his arguments with Mister Lee usually ended with Sammy defending the size of La Ponderosa to the other residents.

For Sammy, this was probably a calculated method of bringing out in the open the resentments, jealousies, and plots he was sure were brewing against La Ponderosa and against himself. Like Mister Lee, Sammy spoke Spanish, but during these arguments he periodically yelled “Speak English!” at Mister Lee, who usually played his part in these show trials by grumbling nonstop, mostly in Cantonese, through Sammy’s rants, even as he continued working on whatever improvement to the House of the United Nations that had set Sammy off.

The House of the United Nations was growing, but intermittently and organically. Mister Lee periodically tied new pieces of cardboard with cloth strips to the outside layers then went inside and removed older inner layers from whatever area he newly covered, thereby slowly expanding his dwelling. In my mind, Mister Lee’s house was an extension of his being, a spiritual work in process.

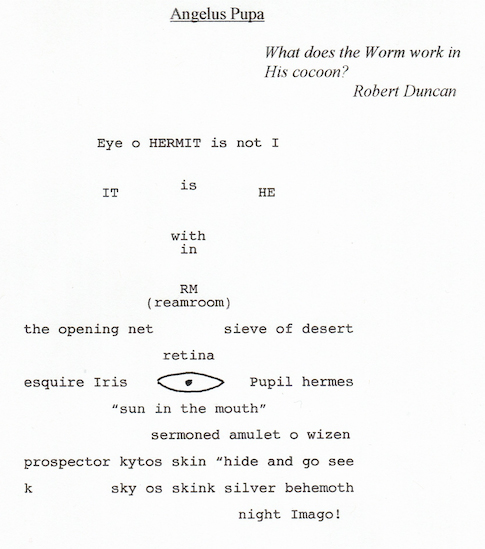

The tipi, Tortuga Pond, and the House of United Nations marked the geographical center of the shantytown. I had begun to think of us as a Trinity, sharing a metaphysical joint destiny. I had pulled some concrete poems out from my old writings because I thought that one or more of them might offer a key, a kind of mystical map to Trinity’s work. But upon reading them, I only half-remembered what the poems meant, as if the author were someone else, and the poems were found objects of unknown origin. I gleaned a different meaning every time I read one.

Along with the Polaroid, I kept these concrete poems as talismans in my special mailbag in the tipi. An epigraph on one of the poems quoted Robert Duncan and spoke directly to me about Mister Lee and his House of the United Nations.

I had named the tipi The Living Museum of the NOMAD MONAD. We took a photo and printed postcards with that name, although no one ever referred to it as anything other than “the tipi.” Similarly, the enclosed acre of elevated land on which the tipi and surrounding shantytown were erected, was simply called the Hill.

“The Tipi on The Hill” had entered into the contemporary mythos of the City.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link.