Entering the Tombs

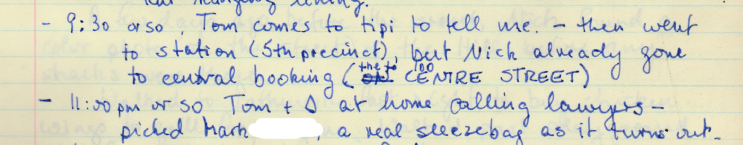

(Gabriele’s journal – December 3, 1990)

(Nick’s narrative – February 3, 2022)

The Fifth Precinct station house was only three blocks away on Mott Street. On the walk there, I realized I was still the same juvenile delinquent I was at seventeen when I first graduated from the local town jail to the county jail. Now here I was making it to the big time again. The Tombs.

After frisking me at the station house before transporting me to central booking, Frick had my wallet in hand, shuffling through its contents. My arrest was the pretense for the real prize he was after. He now knew who I was. “Mr. Nicholas James Fracaro. Sounds Italian.” And then in astonishment, “This guy’s got more credit cards than I do!” Even his silent partner, Frack, found his voice with the discovery. “Too bad, Mr. Nicholas. You won’t be using those where you’re going.”

The ride in the patrol car to the Tombs was only a few blocks, too short for any meaningful contemplation on what might await me. I was apprehensive but reasonably calm. Most everyone on the Hill had been through the system, but unlike them, I wouldn’t be suffering withdrawal symptoms.

When someone got arrested on the Hill, it would usually be at least three days before they returned, if they returned at all. Arrestees needed to be arraigned on their charges before being released. The backed-up court docket slowed down that process. For many, arrest meant an imposed reckoning with their addiction. Averting that pain was the primary reason most postponed their halfhearted attempts to get clean. The few addiction treatment programs available were onerous to enter, so many were waiting for, even partially wishing for, the “bottoming out” event – arrest with its attendant cold-turkey withdrawal. In jail, their addiction would be kept at bay. A subsequent release on bail could be the big step toward recovery.

Arriving at the Tombs, I was allowed to make my one phone call. I knew Gabriele would be on the Hill at that hour, worried about my absence. I called our friend Tom in the East Village and asked him to walk down to the Hill to let her know the score.

When I was seventeen, I had called my mother, pleading with her to find a way to get me out of the Will County jail. I had only been in there less than 48 hours. I spared her my real fear, that I was going to be raped, telling her instead I thought I might be killed. She was able to get me released. I’m not sure how long it took her, only that they were the longest hours of my life.

I had told Gabriele this story, so I knew she would do everything in her power to get me out. What neither of us knew at the time was that nothing could be done to expedite my release. It would be 36 hours before we would see each other again at the arraignment.

In the receiving room with four other inmates, I was searched, fingerprinted and bodily examined. Once inside the first holding cell, I immediately understood the power structure, the same as in the Will County jail years ago. Even in the overcrowded cells inmates banded physically together in racial tribes. Although Blacks outnumbered Hispanics and Hispanics outnumbered Whites, violence was mitigated through this alignment. With an unspoken detente among the groups, only unattached individuals were targeted. And yet, while intimidation was constant, violence was only occasional and quickly quashed by the guards. Perpetrators were handcuffed, arms in front, then returned to the same cell – the tough guy now vulnerable, like a sheep ready for slaughter, serving as a deterrent to others. They also kept rotating inmates from one cell to another so that alliances remained literally only skin-deep. So, while I was in the minority as a white boy, I felt reasonably safe.

The only personal items allowed were paper money under ten dollars and cigarettes. I had a single five-dollar bill but the cigarettes were the more valuable commodity. The Tombs was just a waystation for most. After their arraignment, unable to post bond, the “not guilty” ended up at Riker’s Island to await their trial date. Unable to set up their commissary at Riker’s for a couple weeks, they would be without cigarettes and so did everything they could to procure them here. Most of the altercations stemmed from this imperative.

When I first arrived in the cell, before I noted the racial alliances, a Hispanic inmate was trying to strip a white kid of his pack of cigarettes. I was seated on the floor but impulsively I stood up, not to intervene but to be ready to defend myself if necessary. The perp saw something different and backed away from his victim. “Okay. Okay. I get it. A white boy thing.” He walked back to his group. The white kid came over to me. “Thanks. You want a cigarette?” I hadn’t smoked in over a year but I instantly accepted his offer. The group of four Hispanics attentively watched the exchange.

With just the one cigarette I knew I was addicted to nicotine again, at least for the duration of my stay. In our white-boy group of two, one of us stood guard, while the other sat against the wall resting. Maybe five or six hours later, we were both moved to separate new cells.

In the new cell I walked tentatively toward the two white guys, where I presumed I belonged. One was sitting in the corner shivering from withdrawal. The other was heavily inked with jailhouse tattoos. He reminded me of the brothers at the Hill. I stood far enough away that I would need an invitation to join them.

“You got a cigarette?”

“No.”

“Then you’re more worthless than shaky jake here. At least he’s got cigarettes.”

Alright, fuck it. I’m on my own. Let’s see what happens.

Visit this page to engage with Nick about hybrid literary genres crossing the fiction/nonfiction border. This inquiry is being written, and should ideally be read, contemporaneously with the excerpts. For the section that is current to this post, use this bookmark link.