Life Writings

Forty-plus years ago for my thesis, An Autobiography of Jesus Christ, I had to choose three professors as my readers. As the title suggests, there was no defined genre for such life writing back then. The readers I chose, although they were considered “experimental” in their various published works of poetry and fiction, were not completely on board with my thesis proposal. All three objected to a statement in the outline asserting that the autobiography would always be in process as I lived it, finished only when I died (not necessarily by crucifixion) or when I turned 33 years old.

University graduate writing programs have transformed dramatically since 1980 when my alma mater – U of I, at Chicago – was the only university in the country offering an MA in Literature with a Creative Writing specialization. Today there are myriad MFA programs being offered in the oxymoronic “creative nonfiction” genre. They recognize that the postmodern era of life writing has destabilized the ontological border between autobiographical nonfiction and fiction.

“Explore a broad and vibrant curriculum of nonfiction writing, including memoir, personal essay, lyrical essay, autofiction, experimental and hybrid nonfiction, and literary journalism. Learn more about creative nonfiction.”

An Autobiography of Jesus Christ, and most of my writing since then, including the narrative I am simultaneously writing in serialized excerpts/posts here, would be classified under one or more of these subgenres of creative nonfiction. And of course all of us are now practicing some facet of life writing through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, etc.

This page will stay in process. It will be an ongoing personal essay that examines its title and its rubric: Life Writings. Readers are encouraged to engage in the comment section about the nature of their own creative nonfiction.

********************

CASE #1

The concrete poet is poised to write their autobiography.

How should they classify the creative nonfiction they are poised to graffiti onto Brooklyn streets?

No, correction, they are poised to wright.

I.e., the rite of life writing is that you first need to build the life before you can write the life,

Or, if you prefer, you may write the life as you live and right it with your writing.

What’s wrong with this picture?

Bump in the Road

15-Second Biopic of a Concrete Poet

For the concrete poet, the page is the canvas where words, letters, fonts are employed to confer meaning (color) beyond conventional usage. What is created is less poem and more object. The page is less the conventional fiber paper (now the digital screen) and more a stage for the poet’s metaphysical performance art.

The actor under the single follow spot or street light; the stage is the same. That light above is more than just a metaphor, it is the metaphysical light of their singular star. Their stardust’s minute of flesh that owns the stage as Words, the Speaker, Deeds, the Doer. The actor faces an audience, but what fills the space behind them? The ancestors gather there and enter through the DNA to speak and do through their vessel, the Actor. Words, the Speaker, Deeds, the Doer affects those just beyond the flesh gathered presently as witness. Their curtain call gesture is gift to the Seventh Generation.

The page/stage is the night sky where the silent k night performs.

That which is below is like that which is above, and that which is above is like that which is below, to perform the miracles of one only thing. ― Hermes Trismegistus

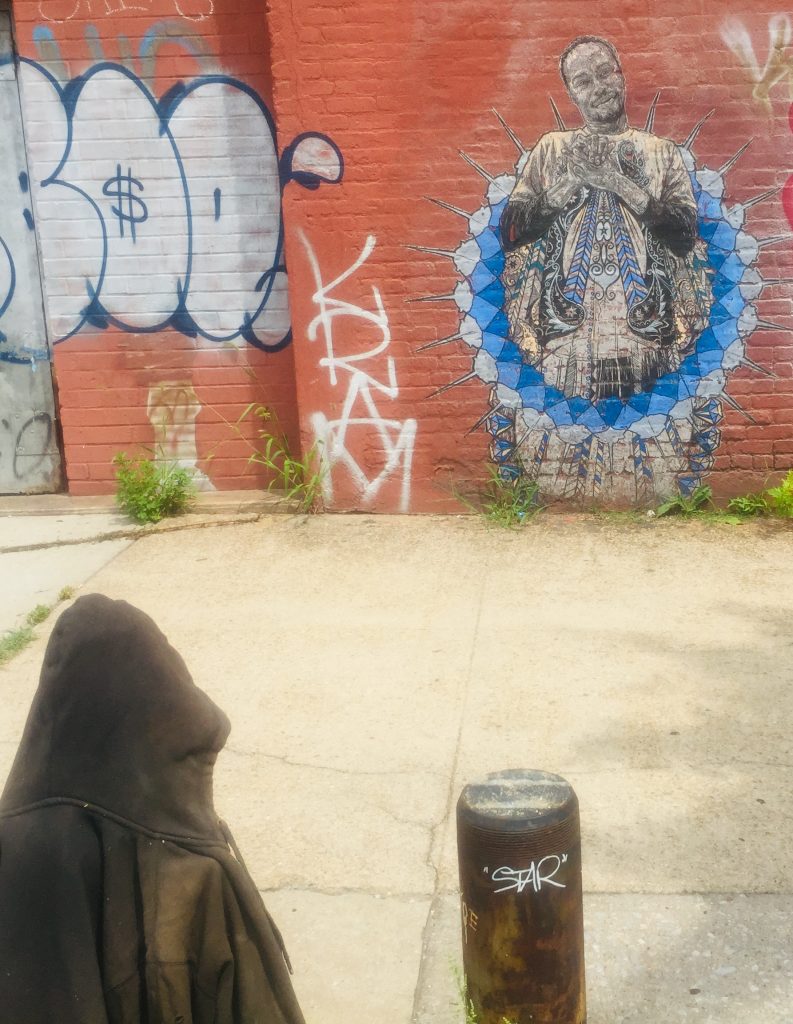

At first glance, you may not notice the difference between these two WHITE BOY tags. On further scrutiny, you would see subtle differences, but you would probably still rule both tags to be created by the same hand. Yet for demonstration purposes, consider that one is the real WHITE BOY and the other is the fake WHITE BOY.

The WHITE BOY tag is more than words on the digital screen. Once it was an object that existed on many building walls throughout NYC’s Fifth Police Precinct of Chinatown and the Lower East Side. We think of graffiti, like other painting, as being a two-dimensional art form. Yet when WHITE BOY is sprayed over another piece of graffiti, hasn’t a third dimension been created? Hasn’t an actual object been created? The tag not only negates the graffiti under it, WHITE BOY is now the building itself and that building is now a physical marker of a territory. The surrounding streets and drug trade are owned by WHITE BOY.

Thirty-some years ago my fake WHITE BOY tag was indistinguishable from the real WHITE BOY tag. Like a sealed time capsule, this WHITE BOY tag holds the essence of my life experience at that time.

The trepidation I had years ago about learning to mimic and enact the WHITE BOY tag is similar to my fear of recreating from memory the tag today.

The memoirist cannot write about an experience that did not happen but what if the memory is so compromised by trauma that it is inaccessible except as a dreamlike blur of intense emotions juxtaposed with minute flashes of “what really happened.” If you render what you believe to be the essence of the experience that has been retrieved from that corrupted memory chip, but you know that the data is not “what really happened,” have you crossed the ontological border between nonfiction memoir and fiction? Does it matter? To you? To the reader? Hemingway set the goalpost.

A writer’s job is to tell the truth. His standard of fidelity to the truth should be so high that his invention, out of his experience, should produce a truer account than anything factual can be.

I had a living model of the tag to mimic back then. Now I have only a vague visual memory and perhaps a trace of muscle memory in my right hand and arm.

Tech has been phasing cursive writing out of today’s education but there was a time when everyone created their signatures from cursive. And of course, over their lifetimes, everyone has transformed that signature they first “made up” in grade school. Sometimes the transformation was drastic, necessitated by a name change, but other times just by a creative urge or whim. If we had to recreate our grade school signature today, how accurate would it be?

I try to pull the memory out of the ether, signing the digital paper in front me hundreds of times with improvised tags. I realize that these signatures are mostly “made up,” but what is the essence of memory if not the reinvention of the actual? I see a certain replication emerge and I choose the exemplar of that repetition as the final tag.

Remembering how I had broken down WHITE BOY into elements before I first sprayed it on a wall, I break down this template of WHITE BOY the same way. Similarly, I name each element as I remember doing before. Discovering the “bump in the road” element feels like proof that the metaphysics of the process are sound.

I am writing what I remember, what I am living.

I count the number of steps from my apartment door to the masterpiece that has been painted over, disrespected. 723 steps. Not sure why I need do this. Perhaps at some instinctual level I know I am about to lose my way home again.

I slash WHITE BOY onto SV’s throw-up, onto the toy’s disrespect to a king.

By putting my Black Book online I have ignorantly placed myself in jeopardy with both the street and the authorities. They all now know my name and where I live. Similar to what the fake WHITE BOY did three decades ago.

Arrogant self-righteousness only belatedly reveals itself, and once again, the fake WHITE BOY has become the real.

Today, in the digital world, I could instantly delete the documentation of my crimes or hide access to them behind a password.

“whiteboy”

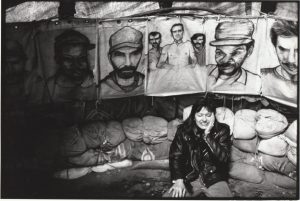

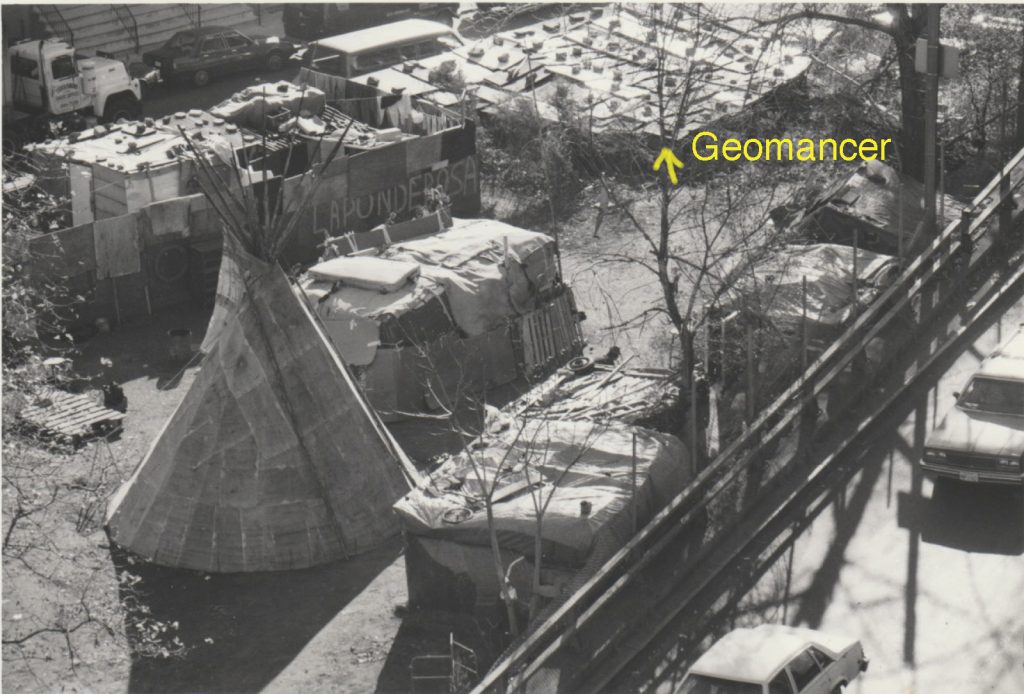

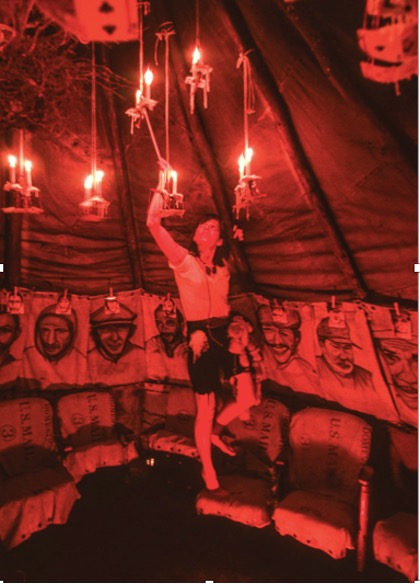

“Gabriele had sewn the tipi cover out of 78 mailbags, the number of cards in a Tarot deck. The inner lining consisted of mailbags on which she had illustrated her oil-stick interpretations of the Minor Arcana. Everything about the tipi in the shantytown, from conception to erection, had been initiated through my readings of the Tarot.” excerpt: Mister Lee

And now we were living an evolving Tarot – interpreting and revealing at both an unconscious and conscious level our lives as we lived them. “The portraits of our neighbors that Gabriele drew became living court cards. Hung as the inner lining of the tipi, her models were endowed and special. They had become the Kings, Queens, Knights, and Pages of the Hill. The tipi was a gallery lined with the portraits of royalty.” The Living Museum of the NOMAD MONAD. excerpt: Geomancer

Each portrait reveals the character of Gabriele’s model. For me, her interpretations go even deeper. Of course, it is only in reflection, in memory, that I see the archetypes revealed. Living and sleeping under the gaze of the portraits, while simultaneously interacting daily with the real people they represented, the archetypes primarily provoked at the unconscious level. The Wordsworth quote instructs on not just poetry, but on all life writing.

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.”

The Tarot archetypes parallel closely with Jungian concepts of the self and personality. For many on the Hill, their addiction, their shadow, had almost completely eclipsed the self. The Hanged Man is the reigning archetype in many of the portraits.

Mister Lee’s portrait was the odd man out, so different from the others. Working on top of his cocoon, he is The Fool, the Sacred Clown. An amalgam of jester, sage, magician whom I had sought as mentor.

My writing in the narrative is primarily a meditation on the court, the portraits of the Kings and Queens, the strong emotions that their personalities and selves still evoke in me. How their souls still haunt and hunt me.

How the Hill’s evolving landscape remains forever as dreamscape.

The Geomancer sees through time. He sees a tree grow in the earth and then die. He sees another tree grow and die in the same place. He sees the earth paved over with stone. He sees a man and woman standing on a stone ledge overlooking all creation. He watches closely as the anima mundi animates the world through time.

Traditionally in memoir and autobiography, the author and narrator are the same person, and they tell “the true story of what happened.” Autobiography is a record of chronological events. In memoir, events may move back and forth in time, with emotional truths coloring the facts. This emotional coloring may obscure “what happened.” Since memory not only records events but also transforms them, in memoir, vague, even faulty memory may contain vivid emotional or psychic truths that can be used to tell “the true story.”

Both memoir and autobiography might allow an older narrator to reflect on their younger naïve self’s experience, almost as if they were another person more qualified to tell the true story. Like a parent supplying the context to their child’s story or the psychologist analyzing their patient’s experience. In this way, it’s possible for a memoir to simultaneously convey two different stories of the same events. That was then, this is now. Now is the author and reader appraising then, the more “naïve” person and/or time.

Fiction has another device at its disposal. With the naïve or unreliable narrator, the author creates a place of ironic observation from where the reader views the narrator’s story.

The Hill story will be difficult to classify into a genre. I am writing this accompanying “Life Writings,” also episodically, to categorize and clarify the story’s narration, both for myself and for the reader.

No doubt the narrator of the Hill is me, the author, relating events from thirty years ago as memoir. But as analogy, consider The Matrix Resurrections. Thomas Anderson (Neo on the red pill) is the author of The Matrix video game series based on his faint memories of Neo on the blue pill. If the author and reader of the Hill are on the same red pill, then geomancy, Tarot, and the other auguries that Nick/Chief employs will be categorized under pseudoscience. Chief’s medicine bag which contains his ghost shirt, magic poems and Polaroid will be categorized not as actual talismans, but as proof that Chief is suffering from delusions and the story is a work of fiction with Chief as the unreliable narrator.

But the author and his narrator were both on the blue pill thirty years ago and this is their true story, their memoir and not a video game fiction. It is left to the reader to decide whether the story belongs to the world of fiction or the factual world of autobiography. Swallow the blue pill or red pill before you read.

Removed by thirty years from my life on the Hill, it is difficult for me to remember the person I was back then. Gabriele’s journal does serve as a prompt, but often the facts and events she details do not exist in my memory, and sometimes my corresponding memories even contradict the facts of the journal.

No matter, it is the skinny of the story that is sought. The truth of the story.

Similarly, despite all the details in Gabriele’s journal, I have the same difficulty remembering the exact cultural and political milieu of New York at that time, except for the aspects that I personally experienced.

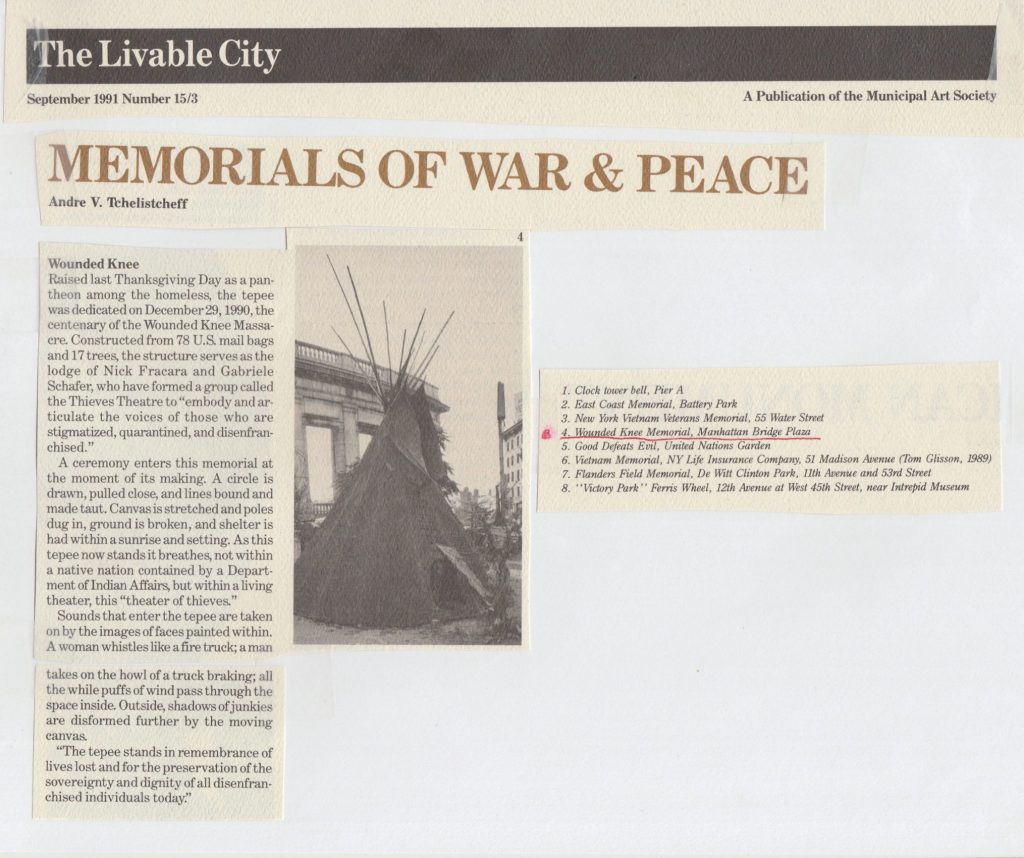

How is it possible that a tipi by a white boy could be erected in a shantytown and not immediately produce a negative outcry from all corners of the city? How was this art whitey activist not immediately ostracized by his cultural and artistic peers?

We worked not only with the support and collaboration of our peers at the time, but after the tipi was erected, we were in direct counsel with many prominent cultural, social, and artistic organizations. We were even in continual contact and conversation with the Borough President’s Office. The Native American community was, individually, positive and negative and tentatively supportive and offered to adopt us, and was also, collectively, silent. If there was any notion of “cultural appropriation” (a term not in the common vernacular at that time), no peer, organization, or institution so much as hinted at it.

We held a dedication ceremony on the centenary of the Wounded Knee Massacre. The following September, 1991, the venerable Municipal Arts Society listed our tipi as one of New York City’s eight “Memorials of War & Peace” in its publication, The Livable City.

Coincidentally, or prophetically, the film Dances With Wolves was released on the same evening we erected the tipi, Thanksgiving eve, 1990. The film was hailed by critics and Natives alike for its depiction of Native Americans. Breaking with Hollywood’s make-believe history of Cowboys and Indians, the movie portrayed the Lakota people honestly and sympathetically, highlighting their spiritual grace and humanity.

The film’s box office success is also credited for reviving the Western genre of moviemaking which had been waning in popularity for the past couple decades. Many Americans had grown up watching Westerns, which was the most popular Hollywood genre from the 1930s through the 1960s.

Like most children my age, I grew up playing Cowboys and Indians, under Hollywood’s direction. I grew up on a farm in an extended family that included three other households of uncles, aunts, and cousins. Other than school, we spent most of our days as children playing on the farm with my sixteen cousins.

The small town close to the farm was Lemont, Illinois. Every year on Labor Day weekend, starting in 1952 and continuing to the present day, the town held its annual Keepataw Days Parade and celebration. My mother and aunts earlier in the year would have tailored elaborate Halloween costumes for my cousins, siblings, and me. They took the Keepataw Days Parade as the other annual challenge for their skills. My father would drive the farm tractor and hayrack to the parade with the rest of the family meeting him there.

Without knowing the actual Native history of the land, the townsfolk of Lemont, Illinois, who started the parade in 1952, probably knew Keepataw (the original name of the town) was a Native American name in the same way they knew that Illinois was. In the same way my alma mater, the University of Illinois, knew history when they connected the image of the Native American “Illini” to students, athletes, and alumni. The sports teams were and still are the University of Illinois Fighting Illini.

This romanticized identification with Native Americans is not unique to Keepataw, Illinois, but it does instruct as microcosm, reflecting how the whole of America has appropriated Native culture. The genocide is forgotten, replaced with the fairytale that we all now share the same American heritage. This allows the systems of dominance and subordination to continue.

The recent controversies over sport team mascots encapsulates how late White America is in recognizing that the same system used to colonize, assimilate, and oppress Native culture continues to this day. Collectively, and individually, white Americans have been slow learners of the true history and their own personal culpability in its making.

Incredibly, the Lemont High School sports mascot was once Lemont Injuns. The wordpress spellcheck app I am using corrects “injuns” to “indians.” And this is exactly what the Lemont school board did. The name was Lemont Indians from 1948 to 1968. It was changed to “Injuns” in 1968, remaining as that until 2006 when the Board of Education changed the name back to “Indians.” Amidst strong controversy. On Monday, July 19, 2021, the Board of Education decided to discontinue the logo and mascot of “Indians.” Amidst strong controversy.

The sins of the father. Difficult to acknowledge as your own, then difficult to repent. A life-long and generations-long journey of acknowledgment and repentance of original sins.

It’s difficult to decrypt the message my family was trying to convey with our parade float the following year. As kids, my cousins and I remembered it as a “United Nations” theme. But I see from the photo below of the 1959 Keepataw Days float, that the words “LET FREEDOM RING” with music notes were written on the apron of the hayrack. And there in the background is my father and his sister, Aunt Mabel, as Mr. and Mrs. Uncle Sam. So more “my country, ‘tis of thee” patriotism than united nations. A variation on last year’s theme, the jingoism and imperialism of the country, the unconscious and unacknowledged subtext that is ingrained in the European-American psyche, is on full display. The adults are as innocent in their ignorance as their children.

I am the Arab on the far left. Cousin Judy next to me is the Dutch Girl. Cousin Jimmy with the black hat is the Spaniard. Cousin Candy is the Eskimo. Sitting in front, Sister Sue is the Scottish Girl and Brother Rick the Indian Boy. Cousin Marty Lee is the Chinaman. Cousin Janet is the Hawaiian. Cousin Patsy is the Mexican. And for the pièce de résistance, the little guy standing in the center in blackface, with a spear in hand, and a bone in his hair, is my brother Steve. Nationality unknown.

Photo credit: The Drunken Irishman

“Life is not about significant details, illuminated [in] a flash, fixed forever. Photographs are.” –Susan Sontag

In life writing, whether we document the past, or record the present as journal, the story created is only a representation, the preferred edition of reality. The details and context framed as in a photograph.

“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.” –Susan Sontag

Life writing does the same by fixating experience and memory into a story, a photograph about “what is not there” as much as “what is there.” Classifying the story as memoir or autobiography does not alter its core. Story is a fiction that appropriates “the facts” of its subject and claims ownership. “Once upon a time” I was this person, and this happened to me.

FAMILY MEMOIR:

Nick & Nick merge with Steve & Steve

then Nick & Steve merge with Nick & Bob

The dead ones haunt and hunt you more than the living. They inhabit your dreams even more vividly than they did in life. On the Hill, without fully understanding it on a conscious level, I was reliving a certain period of my life when my brother Steve with his heroin addiction had become the whole of both our lives. excerpt:Family

Our grade school was just a quarter mile down the road. Nick Popovich was the same age as me. We were the only “Nicks” in our grade school, also later in our high school class. Nick and I were both smaller than others in our class, so more than just through our common name, I also identified with him as the other little guy. I probably even admired him a bit. A loner, he was someone nobody ever wanted to fight, always giving as much or more than he received. He was never the instigator, but he also never backed down from a fight, even when the bigger bullies challenged him. Consequently, he was in numerous schoolyard scuffles, earning his delinquency creds early on.

His family had been dysfunctional long before mine. Whereas I grew up on a bucolic farm with an extended family, replete with the adult supervision that came with being involved in Cub Scouts and Little-League Baseball, Nick and his brother Bob grew up alone with their mother and an alcoholic abusive father.

I was never quite Nick’s friend in grade school except for a short time in the winter of fourth grade. There was a large open field of approximately four acres attached to the school playground. In the heavy snows of that year, the concrete playground was cleared to accommodate outdoor activity at recess. However, for that half hour, Nick and I chose the heavy snowfall of the field. We struggled side by side around the field’s perimeter, barely able to walk in the snow above our knees, as through we were on a mission.

I probably first saw Nick one day walking it alone and joined him. We never talked about why we were doing this, but we both knew it had to be done. We walked that mission all that winter. This is one of my most vivid memories from grade school and one of the few I had about Nick. I now find it strange that neither of us ever talked about it, then, or later when as teenagers we became close friends.

Nick’s brother Bob was a year older than us. In grade school, he was even more of a loner than Nick. He too was always in fights, but unlike Nick, he instigated most of them. It was the summer after I graduated from grade school that I started hanging out with Nick and Bob. My brother Steve tagged along. Two years younger, only twelve years old, I know only now where I was leading him.

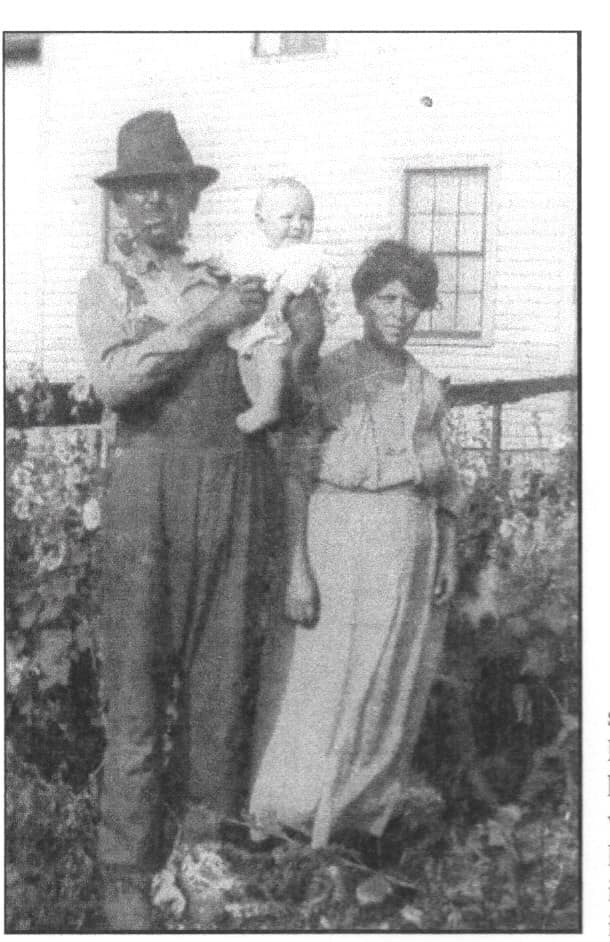

The walk to the Popoviches was ten minutes up High Road to the corner of Route 171. Just before the corner, we took the shortcut diagonally through Calvary Cemetery, then the bowling alley parking lot, to reach their house. My grandfather, Nicholas James Fracaro, was buried in that small cemetery. Steve and I crossed right by him hundreds of times. This grandfather I never knew. This father that my father also never knew. In what hushed voice from that graveyard did he whisper to us as we walked by?

Although I was not his first male grandchild, I became our grandfather’s namesake, as my brother Steve became our father’s namesake. The Roman proverb is “nomen est omen”: name is destiny. Hearing your name said aloud daily affects you on an unconscious level, and the unconscious knows all, past and future. Psychic events are as instrumental in our lives as physical events. This knowledge of the unconscious Jung calls absolute knowledge. It knows everything about Nick and his child Steve. It knows everything about Nick and his brother Steve. It knows how each of their lives is interwoven into one fate.

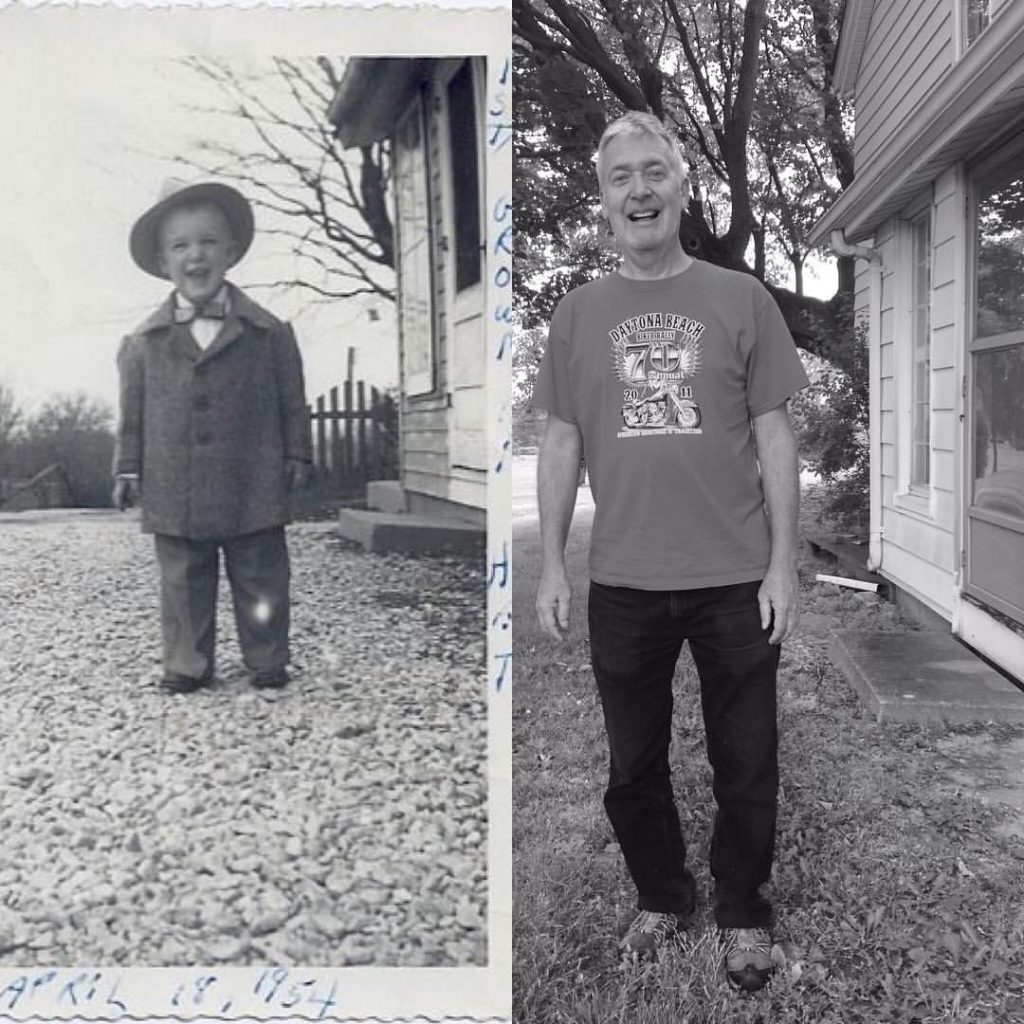

My father Steve was only nine months old when his father Nick died. The physical effect of that death was consequential. My grandmother was forced to raise their eight children alone on the farm without the sole breadwinner. But for baby Stevie, the death was stored as a psychic event in the unconscious. That psychic event would likely be causal in many of the physical events in his life. My brother Steve and I were told the story of our grandfather’s death numerous times from an early age. The oral history was eventually written into a family biography by my aunt and cousin.

Nick died on September 25, 1925 from injuries received when a Chicago and Alton train hit Joseph Ambrosini’s car at the 2nd street crossing, Lockport, Illinois. On September 9, Ambrosini was in his new car driving Nick to see his brothers on Clinton Street on the west side of Lockport. At the time, a crossing guard stopped traffic when a train was approaching. There were no lights or gate. Two parallel tracks cross the road at this location. The guard had stopped the Ambrosini car. After the train had passed, the guard waved the car on. The first passing train blocked the view of another train coming from the opposite direction. The Ambrosini car was waved into the path of the oncoming train. Nick lost a leg and an arm in the accident and died 16 days later from gangrene. Joseph Ambrosini survived but lost an arm trying to pull Nick from under the train.

The story I remember growing up was different, probably because it was so entwined with the other stories I heard about Nick. I wanted to hear everything about my namesake, so I heard many different stories from many different relatives. The story about “the accident” that became fixed in my head, my psyche, was that Nick was doing one of his many side jobs to supplement his income as a farmer. The job was hauling barrels of beer from a brewery to local taverns in Lockport in a horse-drawn cart. The horse’s name was Flora. She was killed when she bolted in front of a train. Nick and the cart were dragged into the train. That’s how Nick lost his leg and later died of gangrene.

No matter which of the many stories told about the physical event was more factual, the psychic event stored in the unconscious was the truest story. The story that became consequential in the lives of Stephen Fracaro and his two sons was told in a hushed voice in that graveyard that Steve and I crossed on our way to the Popoviches.

A mystery story with its veiled circumstances and genealogy of birth and death and rebirth.

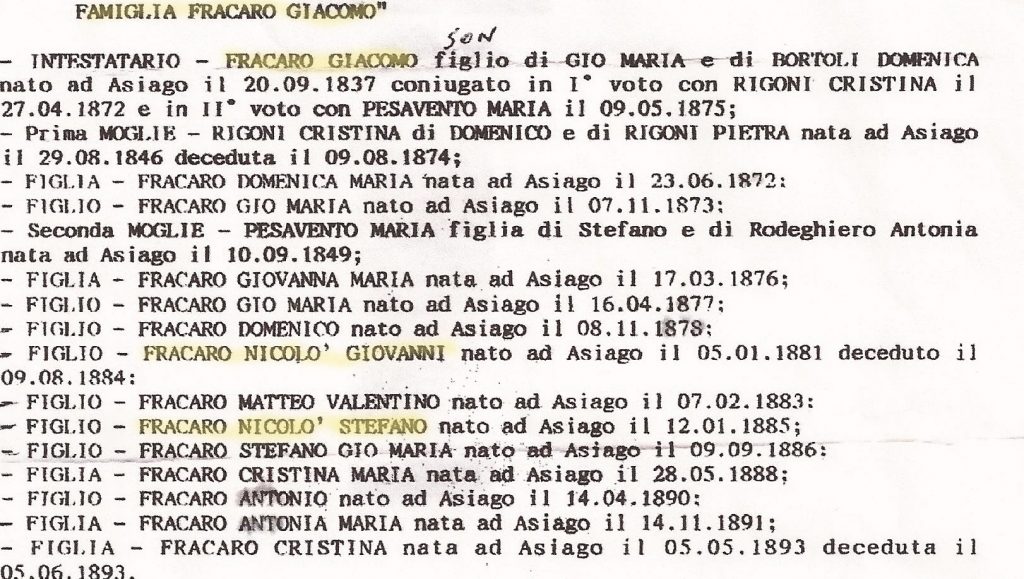

Only after writing the above memoir did my cousin email me the birth records of the family. She had made a copy of them on her visit to our grandparents’ small town in Asiago, Italy. Incredibly, my grandfather’s birth name was Nicolo Stefano Fracaro. He changed his middle name to James after emigrating to America. James (Giamaco) was his father’s (my greatgrandfather’s) name.

Nicholas Fracaro was born in 1885 in Asiago, Italy and died in 1925 in a car accident in Lockport, IL.

Stephen Fracaro was born in 1924 in Lockport and died in 1971 in a car accident in Lockport, IL.

Stephen Fracaro was born in 1954 in Lockport and died in 1978 in a car accident in Lockport, IL..

Nicholas Fracaro was born in 1952 in Lockport and…

It was Nicolo Stefano Fracaro (aka Nicholas James Fracaro) who died in a car accident in 1925. The hushed voice in the graveyard that spoke to his youngest son Stephen and to his grandsons Nick and Steve. The hushed voice that spoke to me as I was writing the memoir. ”Nomen est omen.”

I have owned dozens of automobiles over my life. As I got older and started buying newer-model cars, the odds that the vehicle would “outlive” me became greater. But the hushed voice was coaching me toward a different scenario. The last car and I would die together. The same end story as Nick and Steve, and Stevie before me.

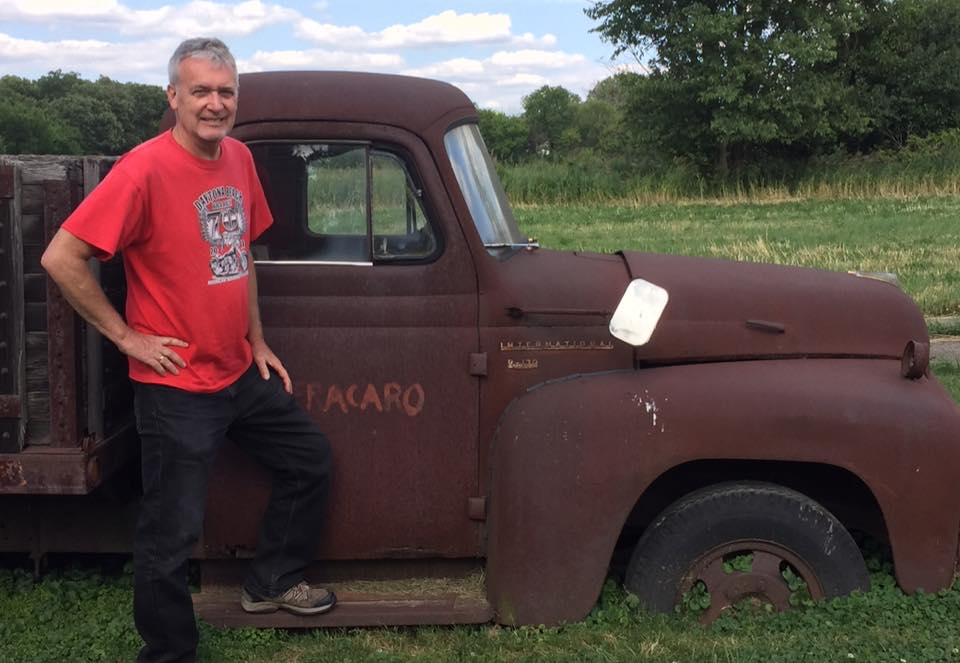

I understand people who purchase vintage cars. The vintage car can capture a unique time and memory, like a photograph. But unlike the photograph, you can take a ride in this three-dimensional memory.

The first “real” car that I bought was a Buick Electra 225, or as it was called, the Deuce n’ a Quarter. Real, because it was legendary, as was the memory it captured. Memories that you summon, then tell and retell over and over, are no longer memories. They transform with each retelling. No longer just ”the true story,” they become something more. The story becomes legend. The legend you live by.

Having grown out of playing Cowboys and Indians, as adolescent delinquents we began playing a new game. Cops and Robbers. For sure, some of our early delinquency was actual crime, but much more of it was just rowdiness, public fist fights and other types of disorderly or inappropriate behavior. The local cops became the authority figures lacking in our family life. Not quite parents, but a few became almost like older brothers.

The earliest memory of cops intervening in our play happened at the supermarket in a small strip mall. The mall, like the bowling alley next to it, was our playground in the summer when school was out. Let’s go play Pennies from Heaven. One of us would climb the wall in the back of the supermarket up to the roof. The others would group in the parking lot in front of the store, in some position where we could see the customers coming and going to the supermarket but they couldn’t see us. We could spend an easy hour entertained by customers trying to figure out how the pennies were materializing around them. And of course an added benefit was that this devised outdoor theatre allowed underage smoking.

We could have entertained ourselves all summer except we decided to add more explosive ammunition. The first water balloon that splashed on the sidewalk near a customer ended our game. He brought the store manager out to investigate. We all moseyed out of the investigation scene, including Bob, who was on the roof, but had been signaled by us to escape. The manager discovered the makeshift ladder we improvised from wooden skids. The jig was up.

Now having water balloons in our arsenal, we sought out more elusive and potentially more dangerous prey, meaning any given adult. We resented their unearned authority over us and their smug compliance to boring everyday life.

About a quarter mile from the shopping mall, we positioned our crew on a hilltop along the country road our house was on, armed with a couple dozen water balloons. Staying somewhat hidden in the tall weeds along the road, we waited for the first approaching car. The four of us then threw our balloons simultaneously. One or more would hit their target and we waited to see if the driver reacted. There was a nearby woods we could run into if necessary. Most would brake but not stop completely unless it was a direct hit. A direct hit was when a water balloon hit the windshield. The driver always stopped if that happened, sometimes opening the door, and stepping out, which sent us running into the woods. Only one time did an angry driver chase us, but either his anger abated, or he was worried about leaving his car in the middle of the road. He gave up pursuit after running halfway across the short field before the woods.

Upping the ante slightly, we added rocks to our arsenal. I say slightly because we didn’t throw these at cars but at the lone tractor trailers that every so often traveled on the two-lane highway past the shopping mall and bowling alley. This always took place at night in the cemetery across the street from the bowling alley. We positioned ourselves behind the gravestones, as if they were bunkers to thwart return fire. The rocks hit the trailer in loud echoing booms causing the driver to immediately apply his brakes, looking for a place to pull over. This was generally far enough away so that we could sneak out from behind our bunkers to the edge of the graveyard and watch him climb out of the cab to inspect the trailer. Mission accomplished.

None of these games brought the police into our lives. However, police reports must have been adding up. And with all the incidents occurring within the same area, no doubt the police had some inkling that local kids were the culprits.

There was a two-acre lot of undeveloped land about a hundred yards from the mall fronting the highway. In midsummer the weeds were almost waist high and dried out. We went into the center, started a small fire, squirting lighter fluid in the weeds behind us as we walked back to the mall. By the time we arrived, the small fire we had started found the lighter fluid and the lot was engulfed in flames. The smoke across the highway stopped traffic in both directions. Five minutes later, the firetrucks and police squad cars arrived, the fire was extinguished in minutes, and traffic was on the move again. Everything back to boring normal. Except for one thing.

A squad car rolled into the mall’s parking lot and pulled up to the four of us. The cop rolled down the widow. I knew who he was. Tully. He was a friend and hunting partner of my older cousin. I had met him once at the two-car garage at his house. During the season I often went out daily hunting with my cousin. One day he had taken me to Tully’s to show me the deer he had recently killed. Both he and Tully always killed more deer than was legally allowed. The Wildlife Commission gave out one tag each season. Without the tag, butchers couldn’t legally accept your deer, so Tully allowed his hunting buddies to use his garage.

“You’re George’s cousin, aren’t you?” I shook my head yes. “Fracaro, right? I forgot your first name.”

“Nick,” I was thinking maybe he knew something. Maybe someone had seen us starting the fire.

“What’s you other guys’ names?”

Steve answered immediately, “I’m his brother Steve.”

“You guy’s are the Popovich brothers, right?” They both nodded their heads but said nothing. “I asked you what your names were?” Nick gave his name but Bob for whatever reason didn’t answer. Tully opened the door, climbing out of the squad car and walked up to Bob. “I asked you what your name was?” Bob gave his name.

Tully had left the squad car’s door open. He walked back and closed it, then turned back to us. “You guy’s know anything about the fire?” We all shook our heads no. “You sure look like you know something. Arson. You ever hear that word. A serious crime. You could end up in Juvenile Detention for something like that.”

We all stayed quiet and tried to look away from him. “Alright guys. Don’t do anything stupid.” With that piece of wise advice, Tully got back into his car and drove off.

As if to celebrate our first encounter with the police, and escaping scot free after committing “arson,” Bob opened the fresh pack of cigarettes we had bought just prior to setting the fire. We usually shared a single cigarette, each taking a couple drags at a time, passing it back and forth, one to the other. But for this momentous occasion, Bob gave each of us our own.

In the 1960’s, if there were regulations restricting the sale of cigarettes to minors, they were not enforced. Kids were routinely sent to the store to buy cigarettes for their parents, and no questions were asked. We bought ours from the liquor store in the shopping mall, but usually through the vending machine at the bowling alley. A pack cost 30 cents. There were two payphones, one at each end of the building. When we needed money, we disabled the coin return on the phones by stuffing a wadded-up paper ball up its shaft. Phone calls cost a dime. It didn’t take long before we had the 30 cents we needed. We never left the coin return permanently blocked so our trick remained an undetected source of income.

I started smoking when I was eleven or twelve. If I am unsure about my exact age, I am positive about the occasion of my “first cigarette” because I retrieved the memory through hypnosis. With the help of the gentle, even voice of the hypnotist on an audio tape, I imagined myself lying on a warm beach near the ocean. The gentle breeze, the sound of the waves, etcetera. “You will now imagine… remember… relive… your first cigarette.”

I stole a Kent from my mother’s pack. There was a golf course directly across the road from our house. I walked its southwest corner perimeter to the Rocks. The Rocks was an approximately two-acre isolated tract of land with large stone formations. My brother, cousin, and I staged our weekly BB-gun wars there. I sat back against a big stone and took my first puff.

As all smokers remember, even if only vaguely, smoking is not an easy habit to acquire. Initially, it is a horrible experience. I’m sure that’s why the Stop Smoking Through Hypnosis tape I purchased had you revisit the details of that unique time and place. For me, having also had alcohol and drug dependencies, nicotine is by far the most difficult addiction. When friends with the habit saw that I was no longer smoking and asked me how I quit, I only half-jokingly recommended the hypnosis tape. “It works for me every time.”

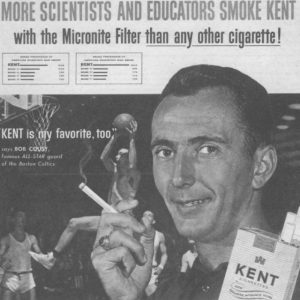

Both my parents smoked Kent, the most popular filtered cigarette at the time. The brand was launched in 1952 around the same time a Readers Digest series of articles was published warning smokers about the cancer studies related to their habit. Most cigarettes were filter-less when Kent hawked its “famous Micronite filter.” Although advertised as “so safe, so effective it has been selected to help filter the air in hospital operating rooms” and used “to purify the air in atomic energy plants of microscopic impurities,” it was later discovered that the filter contained a particularly virulent form of asbestos.

Five years after the famous Micronite filter, Kent quietly replaced it with a cellulose filter, but not before my parents and others had already inhaled some of the 13 billion sold between 1952 and 1957. Crocidolite asbestos is the most hazardous of the six types of asbestos, causing cancers of the respiratory system at rates far higher than any other form. Lorillard, the company that made the filter, has paid out millions in lawsuits over the years. They continue litigating cases to this day but there is an end in sight. Although today a mesothelioma patient is certain to be asked by their doctor or lawyer if they ever smoked Kent in the 1950s, they are all in their 80s or 90s now. A dying breed, so to speak.

With the stolen Kent from my parents, I introduced my brother Steve and cousin Marty Lee to the forbidden joys of smoking. We were now visiting the Rocks more often to smoke than to wage BB-gun wars.

Obviously, when we started smoking our parents were the model, but we needed a peer group to cement the habit into our lives. Brother Steve and I found the peers needed in the short walk up our country road to the bowling alley and supermarket mall. Finding Nick and Bob Popovich, smoking became a central ritual in our lives.

Nick and Bob called their mother by her first name. Any rules on behavior she tried to impose were answered with “Sure Sophie, we’ll do that,” so we smoked without restriction in the basement of their house. We nourished the habit there, but the ritual needed to be enacted in the public sphere with an audience of adults to work its magic.

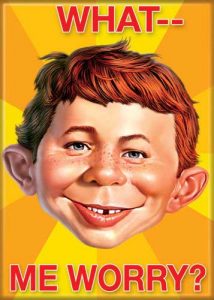

Through diligent practice, we all became proficient at doing “The Nose.” As soon as an issue was published, we’d buy MAD magazine with its mascot Alfred E. Neuman on the cover. The Nose was a facial mask accomplished by widening your nostrils and exaggerating your smile in imitation of Alfred.

We used The Nose in many situations dealing with adults trying to exert their authority. Instead answering the adult’s instructions or mandates with an argument, we stared back and forth at each other with The Nose until our tormentor walked away in frustration.

The fashion back then was for adult men of a certain age to wear fedoras when they went out to socialize in the winter. Before bowling they set the hats on the shelf on top of the coat racks positioned throughout the alley. We had each stolen one as costume for the theatre smoking ritual we performed on Saturdays at the supermarket. The four of us, each wearing an oversized fedora and holding a large cigar, positioned ourselves a few yards from the door. As customers entered and exited, they were greeted by four thirteen-year-old Alfred E. Neuman lookalikes with fedora and cigar.

Editor Al Feldstein wanted to create a visual logo for MAD in the way B&G Foods had created the Jolly Green Giant. He conveyed the essence of Alfred E. Neuman to his illustrator Norman Mingo. “I want a definitive portrait of this kid. I don’t want him to look like an idiot – I want him to be loveable and have an intelligence behind his eyes. But I want him to have this devil-may-care attitude, someone who can maintain a sense of humor while the world is collapsing around him.”

Activist Tom Hayden said, “My own radical journey began with Mad Magazine.” Likewise, my journey in writing and performance, is the struggle to reinvent the legendary delinquencies and mindset of the younger self. One matures in their craft but finding the unique genius in one’s life and art, is all about preserving your perpetual adolescence, the continual questioning of one’s identity and society’s status quo.

Unrehabilitated delinquents face a reckoning with the stark endgame of their misdemeanors once the criminal justice system classifies them as adult offenders.

The year before, I had been locked up with adult criminals at the county jail. That horrific experience should have “scared me straight,” but I was no longer the adolescent farm boy playing cops and robbers. The game had become the realty. I was defining my manhood in a different world now. At eighteen years old, I knew that my latest transgression, although minor in comparison to previous ones, meant a prison sentence.

The local police had visited my home in search of me. The Vietnam War was in full swing then, so not just the police, but the draft lottery would also soon be looking for me.

At this juncture there were only two paths from which to choose. A year older than me, Bob Popovich had survived being locked up in Vandalia Correctional Center for six months. He was one model for becoming a man. The other was to go to war and hopefully die a hero.

To this day, I consider this either/or the most significant event in my life. The choice I made allowed me to become the writer who years later could reflect on his life and the road not taken.

I submitted the memoir/autofiction I wrote about that time in my application to the graduate writing program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Three years later, even though I had never written a play, I submitted it again, in hopes of entering the graduate playwriting program at NYU. I was accepted into both programs solely on its merit. Reading A Cue Stick today is jarring. The unabashed exploration of a traumatic experience and the flawed character/self is equally as disconcerting as the free use of the N-word throughout; it’s a story that would be impossible for me to write today.

Archived writings become artifacts and markers that highlight a unique time and worldview. Dissimilar from the reflective view in a memoir that starkly differentiates between the then and the now of the author, self-reflexivity on collective life writings is more akin to distinguishing the genus and species of trees in the overstory. For instance, the grove of trees that contains A Cue Stick would be designated as Why/How I Became a Writer.

The first and foremost reader of life writings is the writer themself. The process is analogous to that of the alchemist who transforms lead into gold. Likewise, the writer’s transfiguration of life experience into a distilled word object, the story. The true goal of the process is not the creation of this golden story, but the inner transmutation, the liberation of one’s essence from the experience. As Genet wrote, “the rehabilitation of the ignoble.”

But the proof is in the pudding. The material gold was the necessary proof for the alchemist that they had achieved the spiritual gold of their quest. Likewise, the writer hands their story over to the reader for examination.

One can submit writings to a publisher or some other unknown judge. But that word “submit” always bothered me. The adage for academia is “publish or perish.” My life as a writer found the counter to that in “publish or parish.” Finding one’s parish is discovering akin writers and artists with whom you share and evaluate each other’s work. They become the school, the alma mater where you both learn and teach. Alma mater, literally ‘nourishing/bounteous mother.’ Different in species but not genus to the mother who finds the child’s crayon scrawls on paper significant and hangs them up on the wall or refrigerator door as if on display in an art gallery. Where the door is first opened “to make your mark in the world.”

On the first day of my second-grade class, Alma Mater wrote her name on the blackboard.

Miss Weidensee

She then wrote a short poem underneath, animating the words in voice and gesture.

Open your eyes

Wide and see

My name is

Miss Weidensee

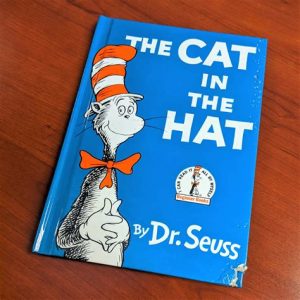

Easy enough to surmise, our reading curriculum was primarily Dr. Suess’ textbooks.

I can’t remember the exact nature of the writing assignment she gave us one day. My only memory is the high praise and celebration she bestowed. Singling out my effort by writing my poem on the blackboard, then reading it aloud in front of the whole class.

I had a cat

He was very fat

He sat on my hat

The hat went flat

And that was the end of that

I was only seven years old, but I knew one day I would be old enough to marry Miss Weidensee and pursue the life of a writer she knew I was.

GHOST SHIRT

Childhood memory is chalkboard

Erased

White cloud of dust

Life writings is shadow tackling in that white cloud.

I have more vivid memories of my seven year old self than any other time in childhood. I credit that to the Cat in the Hat poem I wrote. I must have repeated it over and over in some form throughout my childhood, although I have no clear memory of doing so. But some mechanism has made that year of memory more vibrant than others.

Today, as I write this, March 10th, is my brother Steve’s birthday. And again, it is the memory of a seven-year-old that is evoked.

Steve and I were inseparable as kids. Our father told us never to go up into the hayloft without him. A little red man lived there. He was really strong, and if he caught children alone, he would pull them down into the stacks of baled hay to smother them. But we always found our play in that hayloft and other forbidden places on the farm.

The concrete barn floor where the milk cows had spent the night was shoveled clean each morning. The excrement piled up outside the two doors on either side of the attached grain silo. It would be several days before it would be shoveled again into the manure spreader to be used as fertilizer, so often there was a liquid mote, a foot or more deep, surrounding the silo.

Every day we made it our challenge to walk slowly – step by step, face toward the silo, our backs toward the manure mote – along the silo’s narrow edge until, perhaps inevitably, one day Steve fell backwards into the mote. He was buried in shit from head to toe. I jumped in to pull him out, and we both ran crying to the farmhouse. Our aunt washed us down with a hose. We survived.

As a duo we were always drawn to the dangerous or forbidden. We were fearless in our adventures because there was always the two of us, and in that, we were invincible.

Steve died young. I kept one of his shirts. It’s become a talisman, my ghost shirt. I bring it out to wear only when I know I am walking into a dangerous or forbidden situation.

Happy birthday, brother. I’ll catch you on the flip side, in that white cloud.

When writing a childhood memoir in particular, the most vivid memories sometime stem from disturbing events. But depending on the nature of the experience, the memory is either front and center in the writing, or in the case of traumatic events, partially repressed.

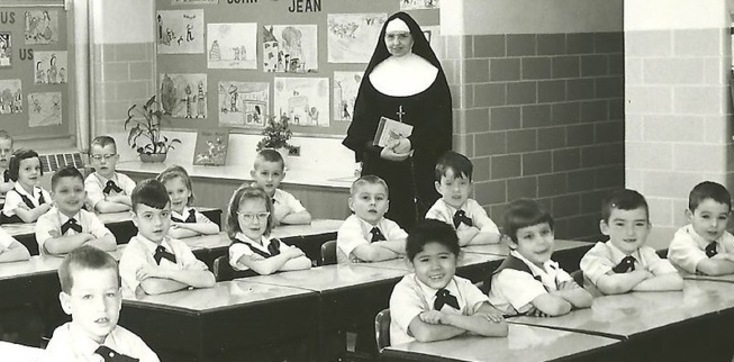

Once, as an undergrad in college, I began writing what I thought would be a short story for an assignment in a writing class. Benedictine University was founded by the Benedictine monks of St. Procopius Abbey in 1887. When I was enrolled in the ‘70s, some of the classes were still being taught by monks from the abbey. The teacher of this writing class was a Catholic ex-nun.

I had been raised Catholic, but except for kindergarten, I had gone to public school. Knowing that the primary reader of this story would be my ex-nun teacher, I deliberately chose my experience in Catholic kindergarten as subject matter. But beneath this conscious choice, there was a deeper unconscious impetus in my writing. Years after the story had been written, and I was once again life-writing, I discovered that unconscious reason: the unearthing of a repressed memory.

The narrator of the story was the child. Of course, my memory of myself as that five-year-old child was vague, but I took whatever flecks of recall I had to start assembling the story. Memory animates the unconscious. Vice versa. The story invented itself. I didn’t realize that I was piecing together a psychic event that was so causative in my life.

Freud termed such memories of early childhood “screen memories,” and although they probably happened, they present themselves distorted and manipulated. Their psychological purpose is to “screen,” to shield one’s psyche from different unpleasant memories of more recent events.

Years after having written the character “Sister Ann Meany,” I was writing a section of “An Autobiography of Jesus Christ” that was emotionally and psychologically grueling about my relationship with my brother Steve just prior to his death. In examining my guilt – the sins I had perpetrated on my younger brother – a repressed childhood memory was revealed.

I grew up the oldest of six children. We were all born approximately two years apart. When I was eleven or twelve, my remiss parents sometimes went away, leaving me in charge of my younger siblings: Steve ten, Sue eight, Rick six, Tom four, and Bill two. Baby brother Bill alone escaped the entertainment I had devised for everyone, only because he was too young to cooperate.

I lined up my four siblings to play the game I called “Mean Teacher.” They stood in a row facing me with the mandate that no one was allowed to move, or even to make any facial expressions. I stood ready with a yardstick to administer punishment for any infraction. After a while, I made one of them switch places with me to play the Mean Teacher.

While the recall of this memory horrified my 24-year-old self as to what my12-year-old self had done, my siblings to this day maintain that they snickered behind my back all the while. It was just a silly, fun game to them.

English Comp Assignment ca. 1974

Baptism by Water

Our class started in the normal way. First sister Ann Marie led us in the Our Father and then the Pledge of Allegiance. But then a break in the everyday routine of kindergarten unfolded. Sister Ann Marie left the room and us twenty five-year-old children to ourselves. I cannot recall the exact reason for her departure, but it may very well have been her own design. She was known affectionately throughout the school by her students and former students as “Sister Ann Meany.” She had obtained this notoriety in part due to her disciplinary actions.

A boy by the name of George was the natural leader of the class and as soon as he noted that she was leaving the room, he set up a lookout at the door of her classroom. He then proceeded to ‘break the ice’ so to speak by throwing a piece of chalk the length of the room and shattering it on the brick wall. Though part of the class was a little slow getting into the partying mood, by the end of ten or fifteen minutes, the whole of us was now enjoying recess. Unfortunately, so was our lookout.

Sister Ann came storming in combat ready. Her thirty-six inch heavy wooden rifle cracked as it zeroed in on the soft bottoms of revolutionaries. Alas, soon the battle was over, and the prisoners placed in uniform rows of desks. “Alright children. Everyone will sit perfectly still and not move an inch or make one sound. Your hands will be folded on top of your desk and your eyes will not leave the cross at the front of the room. You will ask Jesus for forgiveness. You will stay like this for an hour.”

The monster moved mercilessly up and down the rows correcting coughs and side glances and scratches with her ruler. I had so far escaped the sting of correction, but I did not know how much longer I could last. You see, that particular morning, of all mornings, I had neglected the washroom upon awakening. I believe it had something to do with my mother getting up late and barely having me dressed by the time the bus arrived. Anyway, I was in a real predicament. As the hour was slowly ticking on, my need for the washroom was rapidly building. I could not risk raising my hand. Sister might pounce on me and I knew one crack from that ruler would be sure to bring more than pain.

Though my eyes by necessity were riveted to the front of the room and on Jesus, I didn’t pray for deliverance. The power of authority seemed to be with the ruler. I felt the climax approaching within me. I let out a slight yell and jumped out of my desk running. The water in my eyes came simultaneously with the water in my pants, but to my surprise, I had escaped to the boys washroom. I knew she could not follow me there.

Sister Ann had to get Father Raush to coax me out of the washroom. She couldn’t understand why I had locked myself in a stall and wouldn’t come out when she had sent several different boys in there to say she desired me in the class. She said I actually kicked one boy who had tried to crawl under the stall.

When Father Raush came to get me, I felt safe revealing my wetness to him. He was stronger than sister Ann and a lot nicer, too. Being the good man he was, he smuggled me out of the washroom and to the bus. He drove me to the safety of home. He then explained to my mother what happened as I had revealed it to him. He jokingly referred to it as my baptism by water.

The next day at school I was received as a hero by my classmates, who knew not all the reasons for my actions the day before. All they knew was that I had dared to defy an insurmountable power and won. I allowed them to do homage to me. After all, we all need our heroes.

The memoir doesn’t replace memory, but rather, it is a concrete artifact, a “proof” of that past. In the same genre as old photographs, videos, or film, but having an elevated and iconic status. Memory (re)constructed into memoir becomes a linchpin in the chain of connectedness between one’s present identity and one’s past selves. Life writings crystalize not just memory, but also past beliefs, desires, intents, and other mental phenomena of former selves.

Photographic memory is a misnomer. People with the condition hyperthymesia, or highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM), can remember in detail an abnormally large amount of their past experiences, but nothing comparable to the frozen-in-time detail of a photograph. As of 2021, worldwide only 60 people have been diagnosed with HSAM. For the rest of us, the function from which we draw our remembrances of the past should more aptly be termed “quasi-memory.” No two people will remember the same experience in the same way. Neither remembrance is true or false. The memories are just different.

The memoirist’s choice in isolating and detailing events and experiences is a commemoration of not just the individual’s bygone existence, but also that of the collective of family, friends, and others surrounding them at the time. “History is he who writes it.” Because all remembering draws on quasi-memory, the published memoir, by its nature and very existence, appropriates all other individual quasi-memories to become an official record of that time. This document of “his-story,” also becomes their story, i.e., history.

History can be seen as the obituary of a bygone existence. Selectively chosen events of the deceased are highlighted; the rest are dismissed or most often, unknown. Of course, that obituary is often revised or even rewritten, but even then, it is the dominant culture, “the one that wins the war,” which is writing history. The vast amount of history has remained uncharted and unknown.

Life writings is both the contra and prequel to the obituary, the customary (false) narrative of the newspaper article written by family or friends with the help of the funeral director.

Contra to the obit in the obvious way: you are still alive. Also, there is no third party involved in the writing, unless you are blessed with a good editor. Their knowledge and help are equivalent to the funeral director honing the family’s remembrance to its intended audience.

Prequel to the obituary in that the past self is dead. And all stories have an ending.

PLAYWRIGHTS CAN’T SCREAM

Drama and other texts written for performance exist in the liminal space between the written word and the spoken word. The written word in these instances is the (pre)text, the thesis that needs to be completed in the praxis, the enactment of the spoken word. The word needs to become flesh and speak.

ARTAUD VARIATION 2019 PLANCHE 1 —Patrick Santus

Artaud insisted that the playwright or the text should not be the final authority in the collaborative process. As Derrida highlights in his essays on Artaud, the essence of his stance was against the actors’ presence being subservient to the prompter’s (text) presence. The prompter is even more insidious than just that sneaky little whisperer in his dark, dank box off stage but is attached directly to the ears of the actor. “Good inspiration is the spirit-breath [souffle] of life, which will not take dictation because it does not read and because it precedes all text.” [Derrida, La Parole soufflee)

Artaud states clearly his argument against the authority of text in No More Masterpieces.

Let us leave textual criticism to graduate students, formal criticism to esthetes, and recognize that what has been said is not still to be said; that an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives; that all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered, that a form, once it has served, cannot be used again and asks only to be replaced by another, and that the theater is the only place in the world where a gesture, once made, can never be made the same way twice.

Theatre, like other art forms, sometimes produces artifacts. We call these textual artifacts scripts or plays or dramatic literature. The prejudice is usually to conflate these artifacts with theatre itself. But Artaud would be with Genet when he said, “plays should be performed one night and one night only, in a graveyard.”

The originator of butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata, possessed the bootlegged tape of Artaud performing in the broadcast of his radio play “To Have Done With the Judgment of God,” employing it almost as a talisman to endow his work. He would eventually choreograph the dancer Min Tanaka in a performance using Artaud’s piece as soundscape. When Hijikata played the tape for Susan Sontag in 1986 she remarked, “That’s the voice I expected.” Sontag, like many critics and commentators on Artaud, knew of the rumored bootleg tape but had never actually heard it. The “Artaudian Scream” became a critical reference for primordial theatre without anyone imagining an actual audio recording of it existed.

Herbert Blau refers to the scream in his critical tome, The Audience:

Artaud speaks in a later manifesto of actors who have forgotten how to scream. Without the old totemism of beastly essences, the false theatre of mimesis has forgotten more than that. For the scream would seem to be an effraction of memory–the break, the tear, the rending–which is the definitive trace of theater’s birth in the primordial rupture of things.

Mimetic representation… in the theater as in our dreams, creates the part of the audience and subordinates sound to sight. It’s as if the scream has been cut off in full cry… (The Audience p.106-107)

Hijikata seems to have found more in Artaud’s French vocalizations than others. He would invent a method of choreography known as butoh-fu, whereby he would speak words and phrases to his performers that as text resembles poetry but in fact were used to evoke body movements.

We can correlate butoh-fu to the script of a play, especially as it is inherited and communicated only through the notes and memory of Hijikata’s student, Yukio Waguri. We too easily forget that the Shakespearean play does not really exist except in a similar vein, a document organized by and subject to the actor’s memory and (re)enactment.

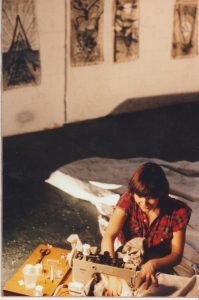

Gabriele has been the indispensable editor of my writings for forty years. Early on, before my hunt-and-peck typewriting skills became sufficiently proficient, she was also my transcriber and translator. My frenzied chicken-scratched writings with #2 pencils on yellow legal pads were indecipherable to all but her. Serving both as forensic scientist and forensic psychologist, she was able to examine the evidence at the crime scene, analyze the mind of the perpetrator, and then present the findings in typewritten pages to the court. From there our relationship as writer and editor continued to grow. Now I never publish anything without her edits and suggested rewrites.

In our joint theatre and art projects outside of writing, there is no clear-cut distinction in our roles, but I generally provide the concept, while she mostly refines, administrates, and actualizes it. I am thesis and she is praxis. But now, in writing the memoir of the Hill, our roles are conflated. She wrote her journal contemporaneously as we lived there. Sometimes the journal relates stories or events that I told her at the time. As I write the memoir, I often refer to her journal, which sometimes confirms, but just as often, contradicts my memory of same.

We always had the latent idea of finding a public archive for the work and the publication of the journal, but only thirty years after our life on the Hill did we go through our archives. Before that, our memory of the experience was too fraught with emotion to retrospectively examine the work and our motives.

NYU’s Fales Library is now archiving the documentation of the project. Gabriele’s journal is published. My memoir is being digitally published in excerpts. Our motive is an ancient one. As ancient as the oldest burial ceremonies and monuments.

Gabriele and I are not the authors, but the ghostwriters of the following proposal, attempting to give voice to the many generations of People and Land. If possible, we would bury our journal and memoir in the Earthen Mound, so that their brief notes would dissolve and meld into the history of all who have lived and will live on the “little hill.” A marriage proposal offered to the living, the dead, and the Seventh Generation.

EARTHEN MOUND

Proposal (May 14, 2022)

My proposal is to install a living Earthen Mound memorial at Forsyth Plaza (Forsyth, Canal, and Chrystie Streets), the highest elevation of land in lower Manhattan, in remembrance of the once-pristine landscape of the Lenape and the four-century evolving history of the mostly unknown and uncelebrated natives and immigrants who made the locale their home. It will serve as a tribute to the Spirit of the Earth beneath today’s “little hill” and to the current “homeless, tempest-tost” hoping to take root.

The title references the Earthen Mounds, the name given to the ceremonial and burial mounds built by two ancient native American cultures, the Adena and the Hopewell. There are tens of thousands of mounds in the United States but many more originally existed before they were bulldozed and casually destroyed.

Conical burial mound built by the Adena culture c. 50 BCE, in the Grave Creek Mound Archaeology Complex, Moundsville, West Virginia.

Conical burial mound built by the Adena culture c. 50 BCE, in the Grave Creek Mound Archaeology Complex, Moundsville, West Virginia.

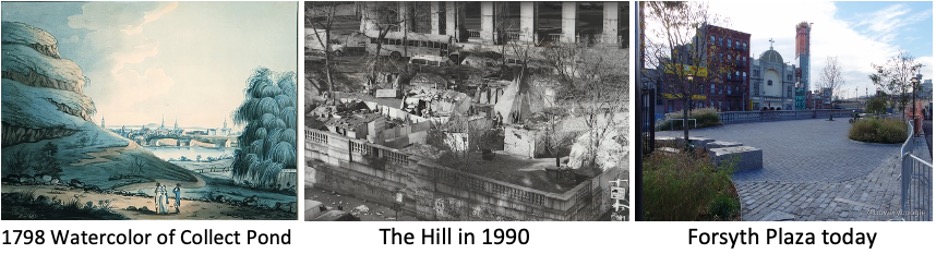

Where is it and why is that site relevant?

The name Manhattan comes from the Lenape “Manahatta,” meaning “hilly island.” The only documented evidence of an Indian village in southern Manhattan was on the banks of a large body of freshwater called Collect Pond. The highest hill in southern Manhattan was on its northeast bank. Next to it was a somewhat lower hillock, where a small band of the Munsee tribe, the northernmost division of the Lenape, lived. The infamous $24 sale of the “hilly island,” between the Dutch and the Indians was transacted here at “Warpoes,” the name of the site. Warpoes translates as “little hill.”

Geographically, Forsyth Plaza today is a little hill – the apex of a slight incline from every direction, the highest point of land in lower Manhattan, as it had been for centuries. This hill is the center of an expanding Chinatown. To the west is Old Chinatown and to the east, New Chinatown. Most of the neighborhood sits atop of what was, three centuries ago, Collect Pond –an evocative and apt name, metaphor for the gradual transformation of the landscape into the present-day collection of historic and new buildings.

In its pristine state, Collect Pond was a body of freshwater that occupied about 50 acres, was 60 feet deep, and bountiful with fish. For the first two centuries of European settlement in Manhattan, it was the main source of the water supply, but as the city grew, various commercial enterprises moved in along its shore in order to use the water. These slaughterhouses, breweries, pottery works, and tanneries dumped their waste into the water, so that by the late 18th century the pond was considered nothing more than a common sewer and hazardous to health.

Beginning in 1802, workmen began flattening the surrounding hills to be used as landfill for the putrid pond, including the two largest hills, Warpoes – “little hill,” called Mount Pleasant at that time – and its adjacent higher peak known as Bayard’s Point. This meant removing the old Bayard family crypt which had been carved into the bottom of the hill. The Bayard family had previously moved their deceased loved ones to burial plots elsewhere in the city, so the crypt was empty of the dead, but not unoccupied.

There was no term like “homeless” back then, but one of the “ragmen” or “hermits” of the city had turned the crypt into his home. Work on leveling the hill was halted when one day the ragman hermit was found dead in his home.

After the landfill of the pond was completed in 1811, high-end houses were built there for the upper and middle classes. The development was dubbed “Paradise Square,” but the landfill had been shoddily engineered. The ground remained naturally a lowland and lacked any sewage drainage. As a result, the houses began to shift in their foundations and to crumble. Buried vegetation released methane. The unpaved streets were often buried in mud mixed with human and animal excrement. Mosquitoes bred in the stagnant pools created by the poor drainage. Paradise Square was definitely no paradise, and by 1820 the middle- and upper-class inhabitants had fled, leaving the neighborhood open for the steady stream of poor immigrants. The five-pronged intersection which lay at the center of this would-be paradise served as its new name, Five Points.

The poorest of immigrants of every ethnicity moved to the Five Points district. That immigration peaked in the 1840’s when Irish Catholics who fled the Irish Potato Famine settled there. The overpopulation, disease, infant and child deaths, unemployment, illegal saloons, gambling, prostitution, and violent crime was unequaled in the Western World at that time.

The original gangs of New York were formed there, and they made Five Points one of the deadliest places on earth. Legend had it that the tenement called the Old Brewery saw at least one murder every night for 15 years. For nearly a hundred years, various gangs from Five Points essentially ran the city. Corrupt police, politicians, and gang leaders were one hand washing the other.

The flipside to the destitution and violence of Five Points is that it has also been touted as the original American melting pot. The first residents were poor Jewish, Italian, and Irish immigrants, and with the end of slavery in New York in 1827, newly emancipated blacks moved in. This cohabitation was the first instance of voluntary large-scale racial and ethnic integration.

As part of the gold rush and the labor market that developed around the building of the Central Pacific Railroad, the Chinese arrived on the west coast of America in large numbers in the 1840’s and 1850’s. When the gold mines began yielding less and the railroad neared completion, the Chinese moved east to larger cities where employment opportunities were more plentiful and they could blend into the already diverse population. Five Points was one such destination.

By 1880, around 1,100 Chinese had made their home there. But the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 halted immigration. The law was a reaction to rising anti-Chinese sentiment stemming from resentment about the willingness of the Chinese to work for less money and under far worse conditions than white laborers.

The Exclusion Act wasn’t lifted until after World War II in 1943, and although only a small immigration quota was given to China, the population of Chinese grew throughout the ’40s and ’50s. What was once the Five Points neighborhood was now Chinatown. When the immigration quota was raised significantly in 1968, Chinese flooded into the country from Hong Kong and the mainland. Chinatown’s population exploded, expanding north into Little Italy and east into the Two Bridges neighborhood.

For much of the 20th century, Two Bridges was mainly populated by European immigrants. Later, Latin American immigrants moved in, especially Puerto Ricans, joining the already diverse Jewish, Italian, Irish, and Greek population. A significant number of Vietnamese and Burmese Chinese joined the melting pot. In the 1980’s the neighborhood became the primary destination for immigrants from Fuzhou, China. They eventually became the majority population, and Two Bridges became known as New Chinatown or Little Fuzhou.

Fuzhou immigrants became part of the larger Cantonese-dominated Chinese community, but many of them were unable to speak Cantonese and had no papers. Their undocumented status meant that their only work was as sweatshop seamstresses or dishwashers/waiters in restaurants. The estimated 600 sweatshops made Chinatown the clothing manufacturing center of the city.

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, Forsyth Plaza, then referred to as The Hill, was the site of NYC’s longest-existing encampment of “ragmen” and “hermits,” home to an ethnically and racially diverse population, many of them recent immigrants. Mirroring the Five Points era, corruption was rampant, as the City was experiences one of its largest police corruption scandals ever, including in Chinatown’s 5th Precinct. Similarly, The Hill was both a melting pot and, with its prevalent criminal subculture, the counterpart of the Five Points era. In the years since the Hill was razed in 1993, homeless people have continuously been drawn to The Hill/Forsyth Plaza, though the City has not allowed fresh encampments to take hold for long.

What is it?

A large Earthen Mound hosting native plants to be installed in Forsyth Plaza in consultation with the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (Our Greenbelt Native Plant Center), and in coordination with the plan to create a night market at the site by the Asian Americans For Equality and Think!Chinatown. Breaking through the concrete, the circular Earthen Mound will commingle with the existing soil beneath the plaza, thereby metaphorically and literally representing Earth’s ever-presence beneath the asphalt of the city.

Who is it for?

The Earthen Mound would include a plaque to make everyone – locals and tourists visiting the plaza and market – aware of the historical, cultural, and environmental significance of the site. The Earthen Mound is ultimately a tribute to Manahatta – the “hilly island” and Land of the Lenape – and will direct visitors to a website that highlights the rich history both of the land and the immigrants who have made their homes on it. The installation would complement the history and character of the area as presented by Collect Pond Park, ten blocks south.

Why now? Why is it a risk worth taking?

As an evolving citizenry, it is important for us to be aware of and to show respect for who and what came before, the generations of land and people preceding us, especially as history repeats itself. Today the earth is in crisis due to climate change. The Earthen Mound – rising from beneath the concrete streets of the City – will increase public awareness of the importance of taking stewardship of our joint history as a People on the Land where we build our homes.

Why is it yours to make?

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, Forsyth Plaza was referred to as The Hill. The site was considered NYC’s longest-existing “homeless” encampment, but it was in fact a tight-knit community and home to an ethnically and racially diverse population, many of them recent immigrants, including Chinese.

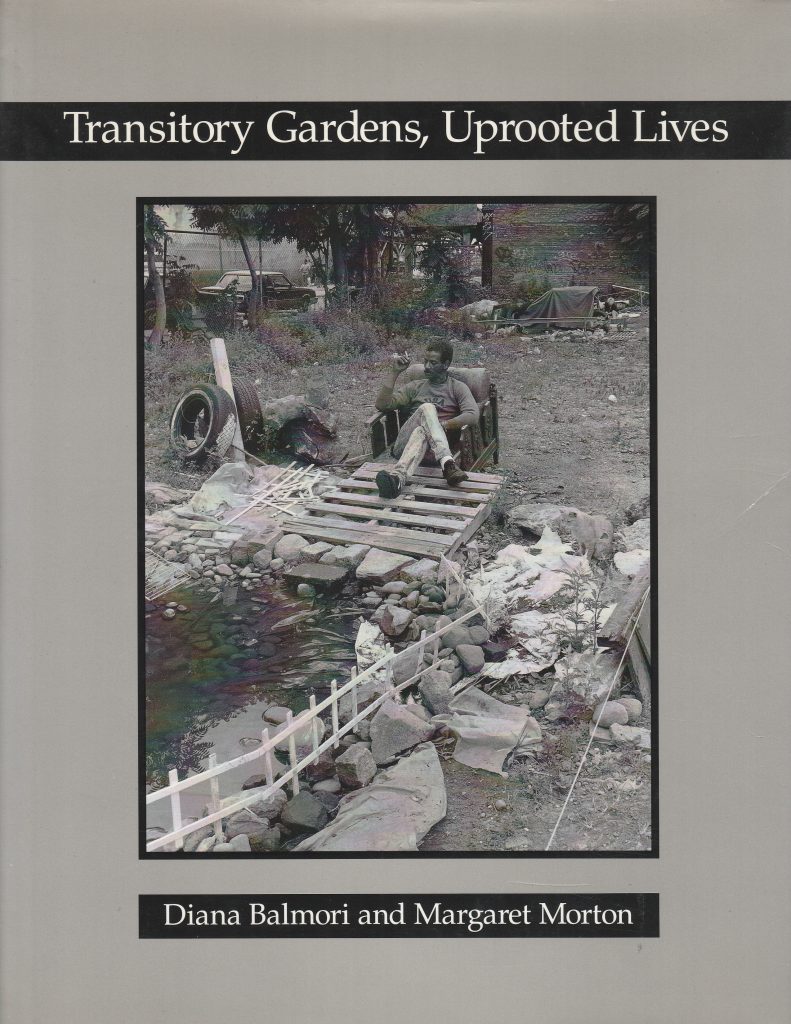

On Thanksgiving 1990, my partner and I erected a Lakota-replica tipi in the shantytown and dedicated it that December 29 – the centenary of the Wounded Knee Massacre – “in remembrance of the lives lost in 1890 and in recognition of the sovereignty and dignity of the most disenfranchised and forgotten members of our society a century later.” A few yards away, the frieze atop of the landmarked arch over the entrance of the Manhattan Bridge depicts a Native American buffalo hunt; and that same Thanksgiving, Dances With Wolves opened in theaters and was later credited with reversing Hollywood’s trend of negatively stereotyping Native Americans. In the summers of 1991 and 1992, I grew and maintained a garden with the help of my fellow shantytown residents at The Hill. Attached below are my portraits of my neighbors and friends (oil sticks on mailbags canvas), as well as excerpts from Margaret Morton and Diana Balmori’s book, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives.

In the summers of 1991 and 1992, I grew and maintained a garden with the help of my fellow shantytown residents at The Hill. Attached below are my portraits of my neighbors and friends (oil sticks on mailbags canvas), as well as excerpts from Margaret Morton and Diana Balmori’s book, Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives.

The Hill was razed in 1993, and in the years since, homeless people have continuously been drawn to the area, though the City has not allowed fresh encampments to take hold for long.

My journal, The Hill, documenting the nearly three years I lived on the “little hill” was recently published by Autonomedia.

Even as we write it, we know the EARTHEN MOUND will be DOA as a proposal to the living powers-that-be. So our motive for writing it is similar to the Supreme Court judge who writes a dissenting opinion to the majority’s ruling. He speaks to the future court more than to his own.

The proposal may also serve as an early draft for a press release for an anonymous group’s guerrilla installation and performance.

For most theatre and performance we rehearse words and action. The word rehearsal in its common definition is almost antithetical to the butoh and other ritual-based performances I do. Only in the intriguing etymology of the word rehearse do I find the right descriptor of the preparation process I use.

From Old French re- “again” + hercier to harrow (soil, earth) again. The funeral “hearse” is derived from the same root, from Old French herse, formerly herce “large rake for breaking up soil, harrow. So to rehearse is the process by which you “raise the dead” for the ritual or ceremony you perform; the process by which you unearth the primitive body movements and gestures that lie deadened beneath the habitual movements of a lifelong domestication.

Waguri was the inheritor of Hijikata’s butoh fu, and used evocative words to stimulate body movements. He once had our workshop ensemble create a performance scene by reading a document that gave a detailed description of the excavation site of a mass grave from the Holocaust. He had the ensemble literally pile themselves on top of one another, and then imaginatively intertwine with the dead of that mass grave. Guided by the butoh fu he spoke, the dead and living flesh merged, and en masse slowly rose from the ground, animated corpses of the walking dead.

From autobiography to fiction to poetry to theater to butoh, the occupation of re-hearsing/re-harrowing the dead (past experience), has been hand in glove in my life as I lived it. Stories do not have endings as much as they become complete. The completed story is also the completed self. Life and writing entwined together in a reoccurring episodic cycle. What does the Worm work in His cocoon?

Please share your thoughts about eitherr “Tipi on the Hill” or “Life Writings.” Join the discussion about hybrid literary genres that blur the fiction/nonfiction border. Subscribe to Nick’s Substack: NOMAD MONAD.

As above so below

I appreciate the context but I struggle with the purpose ie does art fall like a tree in the forest without observation? Does it exist outside of perception? What of the artist who wrangles with

Publication? Does art exist anonymously?

The artwork in the studio vs. the same artwork in the gallery. In process – transforming vs. static, fixed (product).

You submit your poems to a publisher. Doesn’t that word “submit” bother you? The old adage for academia is “publish or perish.” My life as a writer found a counter to that in “publish or parish.” So it’s about finding your parish, i.e., akin artists with whom you share work. (And yes, a poem on a FB page, a comment at this site , etc. is “published.” And now that “The Hidden Life of Trees” is a movie, everyone knows that a tree never falls in a forest unnoticed.) So it’s about finding the parish, the flock, the forest, the school where you belong.